Madonna

In Madonna, Edvard Munch shows us a woman in the act of making love who owns her sexuality.

Edvard Munch: Madonna. Oil on canvas, 1894. Photo © Munchmuseet

Edvard Munch lived in an age when women gradually emerged from domestic life and demanded their place in society. The women’s liberation movement extended across social classes and national borders, and in Munch’s artistic circle there were heated discussions about marriage, prostitution and free love. Perhaps without being aware of it himself, Munch contributed to expanding the perception of a sexually active woman through many of his most famous motifs. In Madonna, he shows us an uninhibited woman giving in to pleasure, and he allows us to understand this as both beautiful and natural.

A radical Madonna

The image of the Madonna is a recurrent theme in visual art. Western art history is full of paintings with this title. These are often depictions of the Virgin Mary, frequently cradling the infant Jesus in her arms or on her lap. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Raphael all created their versions of Jesus’ mother and painted their Madonnas. Munch’s Madonna is a radical departure from all earlier portrayals. The woman we see here is not a young virgin, but the complete opposite: a woman embracing the erotic on a par with men. Munch described the image as a ‘woman in a state of surrender – where she acquires the afflicted beauty of a Madonna’.

Sometimes he gave the image the title Woman Making Love, and he wrote a short text in connection with the image:

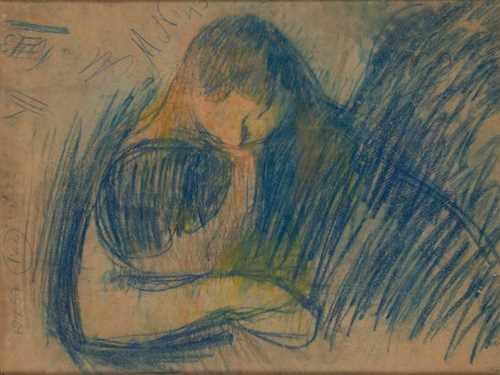

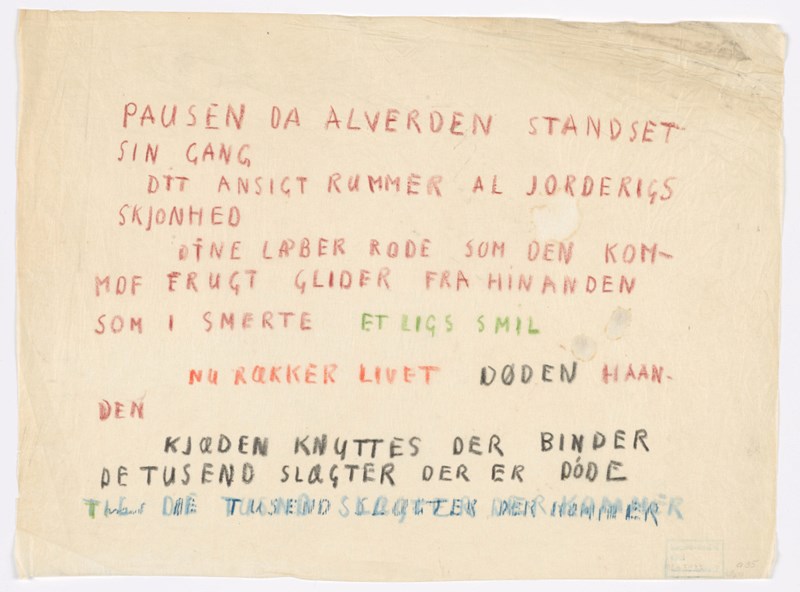

Edvard Munch: Handwritten text. 'The pause when the whole world stopped in its tracks'. Crayon, several colours, ca 1930. From the sketchbook Tree of Knowledge, dated 1892-1930 (uncertain). Photo © Munchmuseet

The pause when the whole world stopped in its tracks

Your face encompasses all of the earth’s beauty

Your lips red like ripening fruit

separate as though in pain

The smile of a corpse

Now life offers death its hand

The chain has been linked which connects

The millennium of generations

That are deceased to the millennium of generations that are to come.

Versions of the motif – Painting, graphics, drawing

There are five painted versions of Madonna, and originally Munch put at least one of them in a wooden frame painted with sperm and a foetus. Several of Munch’s contemporaries found the frame offensive, which may have been why he replaced it relatively quickly with an ordinary one. But the original frame lived on in Munch’s print version of Madonna, where it became a decorative border that was integral to the central motif. This strategy allowed Munch to mask the border for more conservative buyers, while retaining it to satisfy the tastes of more daringly liberal collectors.

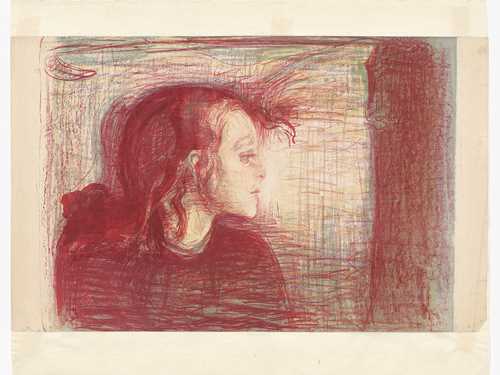

Edvard Munch: Madonna. Lithograph, 1895. Photo © Munchmuseet

The black-and-white version of Madonna from 1895 was one of Munch’s very first lithographs. Lithography made it possible to distribute the image more widely, including to people who could not afford to buy paintings. The motif is a good example of how Munch’s images could be motivated both by market forces and a desire to experiment artistically. After having printed the image in black and white, Munch also made several versions in colour. Initially, he coloured the prints by hand. In later versions, the colours were added as part of the printing process.

Most of Munch’s prints were produced in relatively small editions. In that respect, Madonna is an exception. We estimate that between 250 and 300 impressions of the lithograph are in existence today. Many of these were sold in Munch’s lifetime – the print was undoubtedly one of his bestsellers – although he also gave some away. Even so, Munch retained a large and varied selection in his own collection, and today the museum owns 115 impressions of the lithographic version of Madonna.

Edvard Munch: Sketch for 'Madonna'. Charcoal, 1893-1894 (plausible). Photo © Munchmuseet

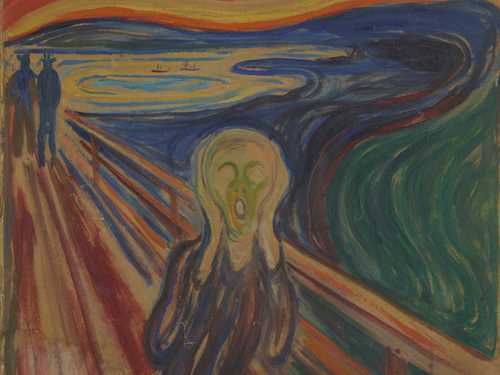

The museum also owns several drawings that show how Munch developed his Madonna image. In the large charcoal drawing shown here, we see how all the most important decisions have already been made: the woman is drawn in portrait format; she is naked from the hips upwards; and the position of her arm is completely resolved. She also has a large, clearly drawn halo. Even so, there are some differences. For example, the woman in the drawing is turning her head away from us. In fact, her whole upper body is seen more from the side than in the final versions of the image. Ultimately, Munch chooses – as he did with The Scream – to turn the woman directly towards us. As a result she becomes more exposed, more vulnerable – but also more alive.

This text is based on excerpts from the collection catalogue 'Edvard Munch Infinite', published in 2022.