When the Room is the Main Character

An essay on Edvard Munch’s The Green Room.

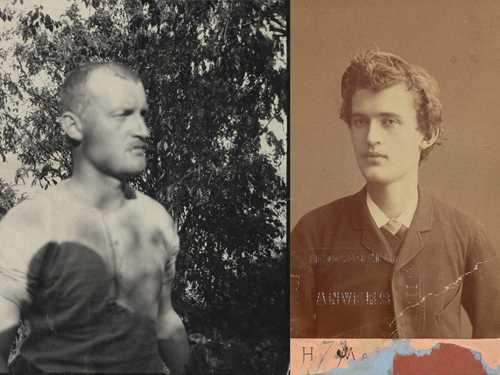

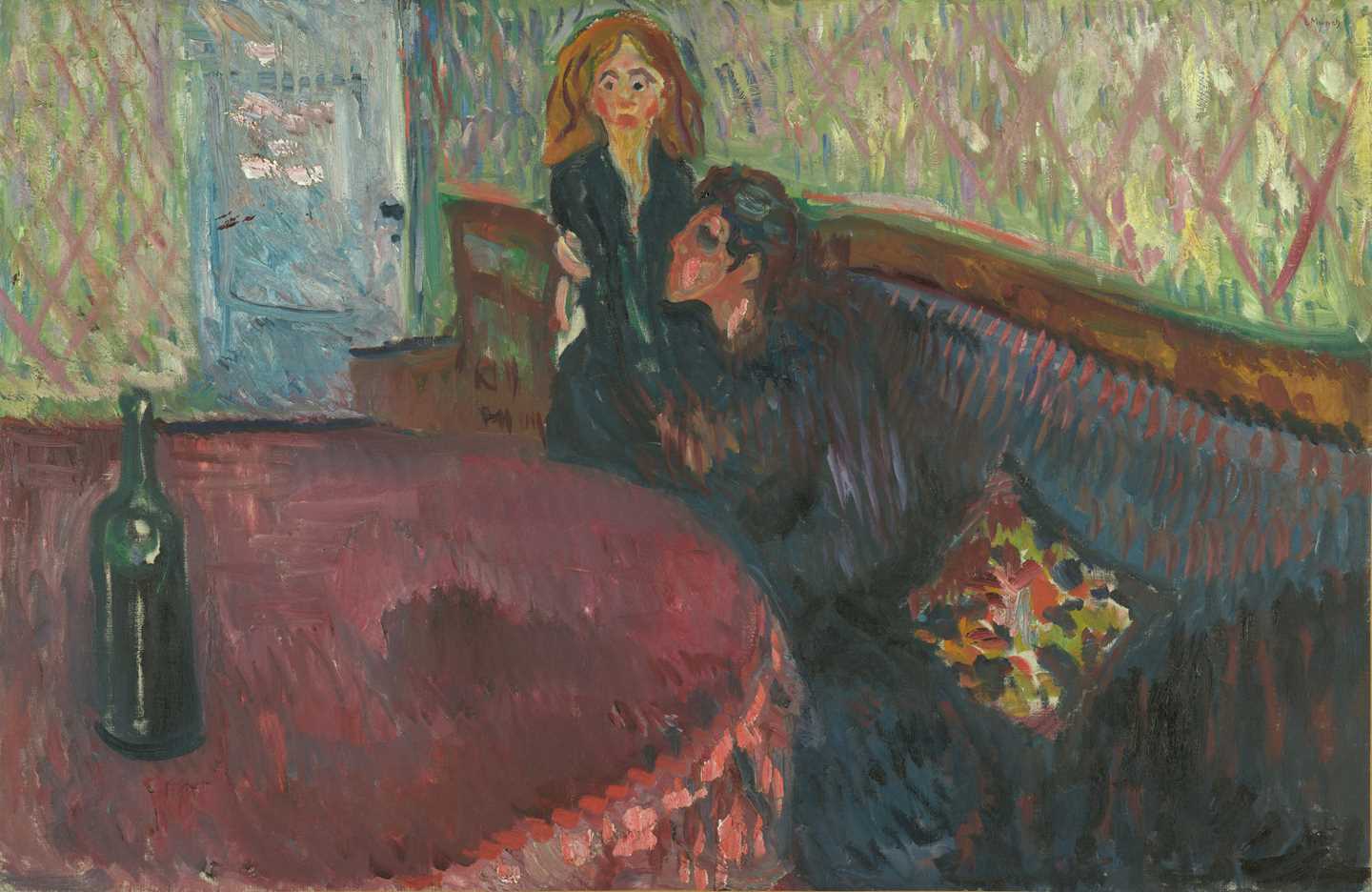

Edvard Munch: Jealousy. Oil on canvas, 1907?. Photo © Munchmuseet

Floral interior design, toxic green colours, a revolutionary theatre director, and Oscar Wilde’s duel with death. Read more about the dramatic and fatal context of one of Edvard Munch’s most unique series of paintings, The Green Room.

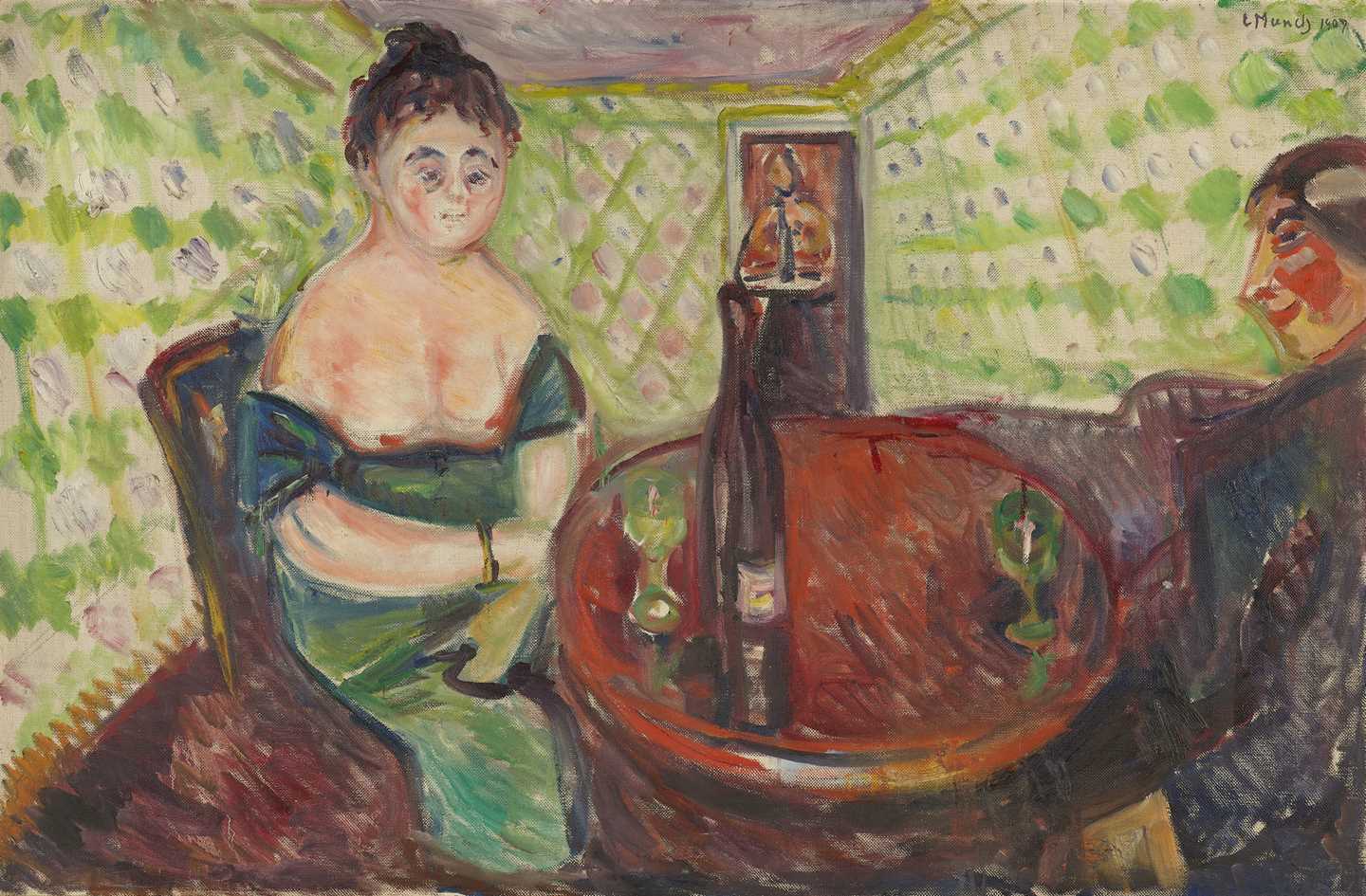

Edvard Munch’s The Green Room (1907) is a series consisting of seven paintings. All the paintings depict a room made up of three green walls, a dark floor, and a low ceiling, populated by human figures. The room is close, intimate, and claustrophobic. The figures – men, women, androgynous characters – are situated around the room in different constellations. The way the room engulfs them resembles a prison cell.

In this essay I will explore the ambiguous world of images Munch created on the two-dimensional surface. How do the spatial aspects, the colours, and the wallpaper affect the figures and the scenes that take place between them? What is Munch trying to convey through this interior that is repeated in the paintings? In these seven paintings, as with most of Munch’s work, the figures themselves are so engrossing that there’s the tendency to completely overlook the background, which is often equally powerful and defining.

A revolutionary chamber theatre. Early in the summer of 1907 Munch moved to Warnemünde, a seaside resort at the Baltic coast of northern Germany. This is where he painted the seven paintings in The Green Room. He also took several trips during that year, especially to Berlin, where he was working on a commission for one of the public rooms in Max Reinhardt’s Kammerspiele, a stage for intimate chamber theatre at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin.

The director Max Reinhardt revolutionised the modern theatre and fortified the position of the director as a creative artist. Kammerspiele, which opened in 1906, was a small stage where the audience members were seated in close physical proximity to the actors, without the usual barriers of orchestra pits or advanced theatre lighting.[1] This led to a more immediate contact between the audience and the actors and created a new bond between them. Rather than seeing the play unfold on stage from a safe distance, the audience got to feel as though they were a part of the performance, that they were in the middle of it, both physically and psychologically.[2]

Munch was in close contact with Reinhardt’s theatre from the autumn of 1906 until December 1907. In this period, he completed so-called mood sketches for Reinhardt’s productions of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (1881, opening on November 8, 1906) and Hedda Gabler (1890, opening on March 11, 1907).

Munch’s Reinhardt Frieze was completed in December 1907 and installed in one of the public rooms of the theatre.

Hypnotic rooms

Several of Ibsen’s plays take place in one room, including Ghosts and Hedda Gabler. While the drama of real life rarely limits itself in that way, the theatre keeps the gaze locked in a “recurring milieu”,[3] as the Swedish playwright August Strindberg described it, something that creates a feeling of hypnotic sameness.[4] In much the same way as the intimate plays Reinhardt produced at the Kammerspiele, the scenes of Munch’s The Green Room invite us to become a part of the green box.

Most of the figures in The Green Room appear to be static. They are either staring at the spectator, embracing another figure, or standing completely still, apparently incapable of moving. The figures rarely interact with the furniture or other props, never touching them even when they are closely positioned. There is no visible source of light in the room, such as windows or lamps. Several different scenes are played out between the figures in this recurring setting that imply sexual transaction, conflict, and alienation.

Unstable perspective

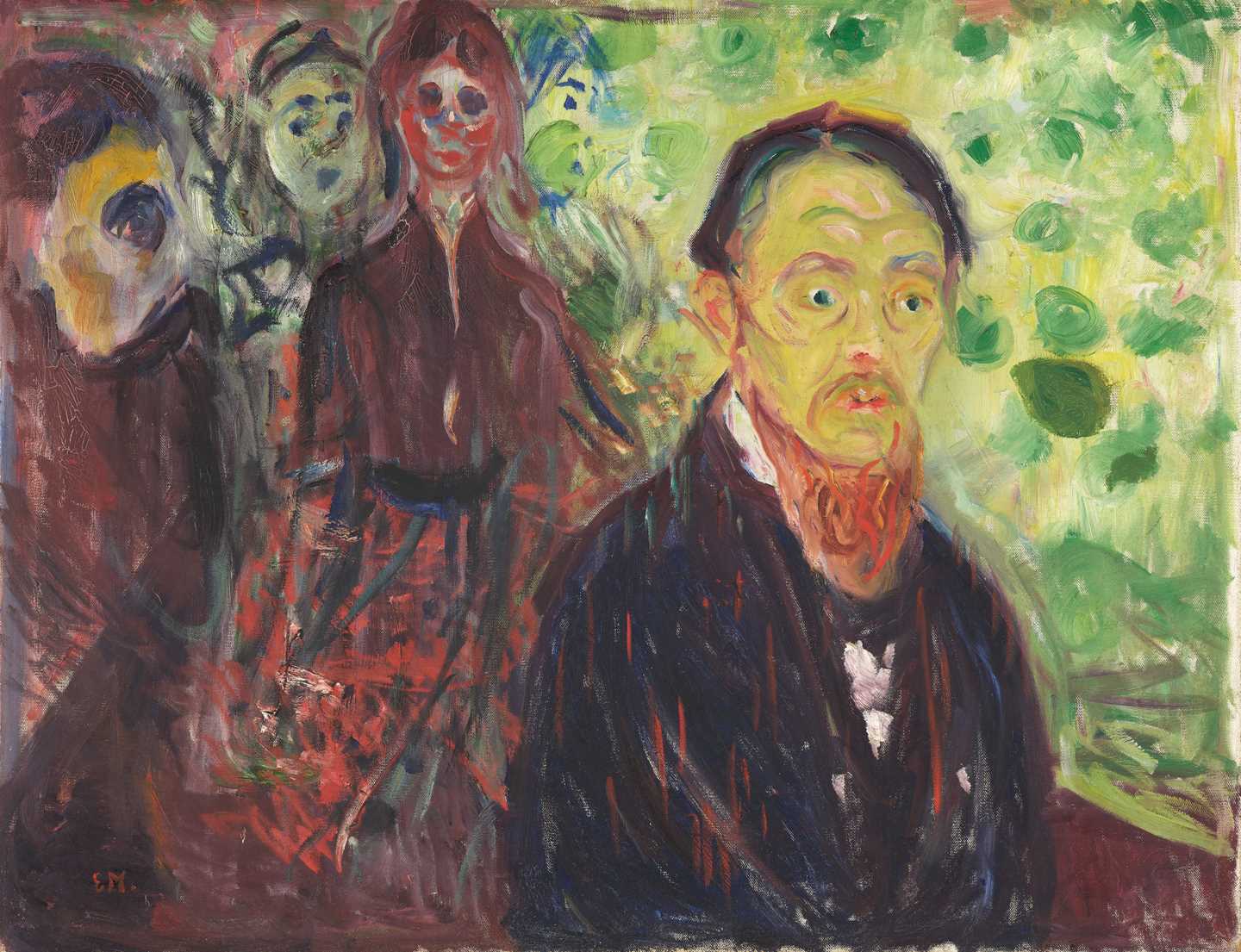

To give an impression of three-dimensional depth Munch uses a linear perspective, seen in the lines that indicate the transition from wall to ceiling, and floor to wall. Munch breaks with the traditional use of linear perspective, for example in The Murderess and Jealousy (Woll 738). The lines in these paintings (if they were long enough) would never converge in a central vanishing point in the composition. Munch creates the illusion of images having a traditional central perspective to create a three-dimensional room on the canvas, but upon closer inspection we understand that he is playing a trick on us. The rooms Munch creates in The Green Room could not exist as actual rooms in the real physical world.

Edvard Munch: Jealousy. Oil on canvas, 1907. Photo © Munchmuseet

Munch also discards other tools for creating depth, such as convincing foreshortening (for example of the sofa and the round table) and shading. In Hatred the figures are presented as large compared to the room, so large that they can step out of it as if it were a theatre stage or a film set.

Edvard Munch: Hatred. Oil on canvas, 1907. Photo © Munchmuseet

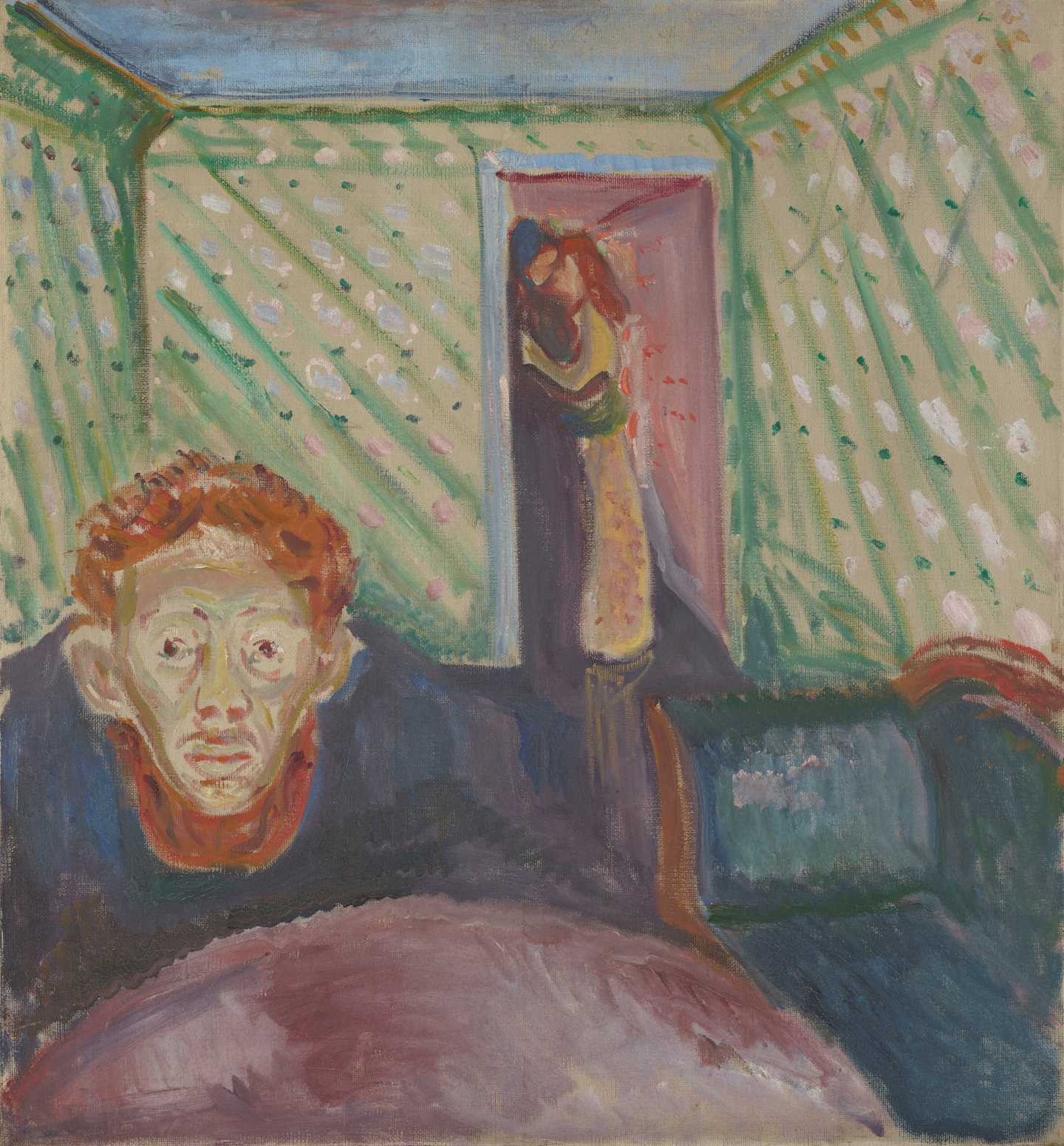

However, in contrast to this, the figures in Desire are small and engulfed by the room and the furniture; they have no way of getting out. Munch’s use of the visual tools of the room, such as perspective, relational proportions, patterns, and colours, affect us as spectators, as well. The spatial relations of the dimensional surface defy our expectations about what the interior is and how a room should be.

Edvard Munch: Desire. Oil? on canvas, 1907. Photo © Munchmuseet

Using the interior to create an identity

How a room should be – and especially how it should look – were topical questions in the 1800s. With a growing middle class came an increased interest in the domestic sphere, and thanks to technological advancements like water distribution, gas pipes, indoor plumbing and even electricity for some, the interior was redefined and associated with modernity.[5] To an increasing part of the population the home became something that should be decorated, and the décor became an extension of the inhabitant’s identity. The British artist William Morris (1834–1896) was an eager advocate of everyday objects as aesthetic products that every home would benefit from, independent of social standing.[6] He argued that all workers should have access to the objects they produced and presented the home as an area for creating an identity and social freedom.

Colours and wallpaper were increasingly used to express gender, social standing, and to define the intended use of a room.[7] In 1833 the Scottish theorist J. C. Loudon (1783–1843) published his comprehensive work Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture, where he wrote:

The colouring of rooms should be an echo to their uses. The colour of a library ought to be comparatively severe; that of a dining-room grave; and that of a drawingroom gay. Light colours are most suitable for bed-rooms.[8]

Wallpaper was to an increasing extent used as to express differences between the feminine and masculine, public and private, and even age and status. Patterns with stripes, vegetation, and floral designs were mostly used in rooms intended for women, such as drawing rooms and boudoirs. Bold patterns in rich, dark colours were used in rooms reserved for the domestic life of men, such as the smoking room, billiard room, and library.[9]

A duel to the death with the wallpaper

The pattern of the wallpaper in The Green Room resembles a diamond-shaped trellis with flowers or leaves/vegetation in the center, but it changes somewhat for every painting. The colour green and the pattern bring to mind the natural world and the great outdoors, but the rooms themselves are claustrophobic and window-less. In this way a contrast is created between the wallpaper’s expression and our impression of the room as a whole. The rough paint strokes are quick and imply brutality and violence.

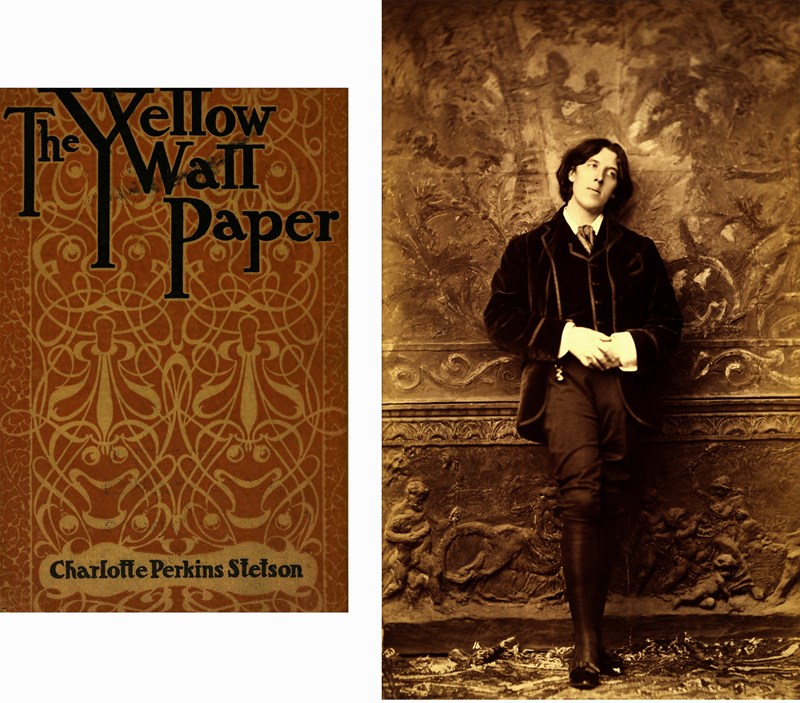

In the early 1900s, the perception that wallpaper could affect mental health and the emotional state of the people in the room was a concern. On his death bed the author Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) is reported to have said that he was fighting a duel to the death with the wallpaper in the room.[10] In the short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), the female protagonist is driven to a psychotic episode that leads her to believe that there are people behind the yellow wallpaper in the room she is locked in. In the end she is convinced that she is herself also one of the people in the wallpaper.[11] Even though it is doubtful that Munch knew about Wilde’s last remarks or had read Gilman’s story, it illustrates a common belief about the connection between interior decoration and health.[12]

Toxic green times

The colour green is specified in the title of Munch’s series of paintings, which tells us it is significant. Synthetic green pigments became available in 1775, when Carl Wilhelm Scheele invented a colour known as Scheele’s green, an unstable colour prone to blackening. In 1814, emerald green was discovered during an attempt to improve Scheele’s colour, which had an unusual radiating tone. Both Scheele’s green and emerald green were used in artist paint, but also in wallpaper, house paint, candles, children’s toys, textile colour, and food colouring in sweets.[13] There was just one problem: both pigments contained arsenic.

The two colours became known as “poison greens”[14] and are considered the most poisonous pigments ever to be mass-produced. When emerald green pigments are exposed to moisture they are broken down to a toxic gas. They were the cause of illness among the workers that produced them and at parties where female guests wore dresses dyed in the synthetic green hues. When the colour was used in candles and textiles the gas was released when used.[15] This changed damp rooms with emerald green wallpaper into pure death traps. Munch painted several compositions of interiors with green walls, in addition to The Green Room, such as for example Death in the Sickroom (1893), The Smell of Death (1895), and Inheritance (1897–99). Considering the health problems associated with emerald green in the 1800s, it does not seem accidental that Munch chose the colour green for the interiors in paintings related to illness and death. .

Edvard Munch: Death in the Sickroom. Pastel on canvas, 1893. Photo © Munchmuseet

The world behind

In The Green Room the room is unstable, changeable, and ambiguous. It is also permeated with information and meaning. In the seven paintings, the green background becomes a part of the story; the surfaces and the room are of crucial importance. Munch did not necessarily use the space to emphasise or convey the figure’s actions, but created instead an ambiguous tension, where the role of the audience – physically, but also in terms of comprehension – is being challenged.

Experience The Green Room

In the immersive experience Poison – An Edvard Munch Experience you can explore this series of paintings in a sensory way. The room is like a strange creature, unstable and unsettling, with unreliable stories and shifting perspectives.

Through the use of floor-to-ceiling video projections, AI-powered morphing visuals, movement tracking, light experiments, and spatial sound, a mysterious being is brought to life, producing a never-ceasing maelstrom of hypnotic imagery. Your surroundings are always on the move and responding to each step that you make.

The experience was availble at MUNCH 22 Oct 2021–31 Jan 2022. Read more about the project

Footnotes & references

- [1] “Every detail counts. The auditorium is no wider than the stage, nor is it lower than the stage; it is not separated from it by an orchestra or a prompter’s box and hence it easily creates an incomparable sense of containment and intimacy. You feel, no matter which row you are in, that you could reach out to the stage. Even the figures in the background of a scene are closer to us than those at the front edge of the apron elsewhere. Not a single breath is lost.” Siegfried Jacobsen, Die Schaubühne no. 46, 15. November 1906, quoted from Lampe, 2012, 111. See also Herald Heinz, 'The Kammerspiele', Max Reinhardt and His Theatre, ed. Oliver Sayler, New York 1924, 148; Arne Eggum, 'Henrik Ibsen som dramatiker i Munchs perspektiv', Edvard Munch og Henrik Ibsen, København 1998, 31.

- [2] Heinz, 1924, 148–149.

- [3] August Strindberg, 'On Modern Drama and Modern Theatre (1889)', Playwrights on Playwriting. The Meaning and Making of Modern Drama from Ibsen to Ionesco, ed. Toby Cole, New York 1969, 16. Originally published in August Strindberg, Samlade otryckta skrifter, 2 vols., Stockholm 1918–19.

- [4] Bert States, Great Reckonings in Little Rooms. On the Phenomenology of Theater, Berkeley 1985, 69.

- [5] Sharon L. Hirsh, Symbolism and Modern Urban Society, Cambridge, 2004, 218.

- [6] William Morris, 'The Lesser Arts ', Hopes and Fears for Art. Five Lectures, London 1911.

- [7] Steven Parissien, Interiors. The Home since 1700, London 2009, 137.

- [8] J.C. Loudon, Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture, 1846, 1014.

- [9] Gill Saunders, Wallpaper in Interior Decoration, New York 2002, 16.

- [10] Barbara Belford, Oscar Wilde. A Certain Genius, London 2000, 133, 306.

- [11] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wall-Paper and Other Stories, Oxford 2009. Originally published in The New England Magazine in 1892.

- [12] See e.g., Alison Chang, Negotiating Modernity: Edvard Munch's Late Figural Work, 1900–1925, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2010, 145ff.

- [13] This part is based on Inge Fiedler and Michael Bayard’s: 'Emerald Green and Scheele's Green', Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, red. Robert Feller og Ashok Roy, Washington 1986, vol. 3, 219–71.

- [14] Fiedler og Bayard, 1986, 229.

- [15] Fiedler og Bayard, 1986, 227 og 229.