The Sick Child

The Sick Child is rooted in deeply personal experiences in Edvard Munch’s childhood. He continued to explore this motif throughout his artistic life.

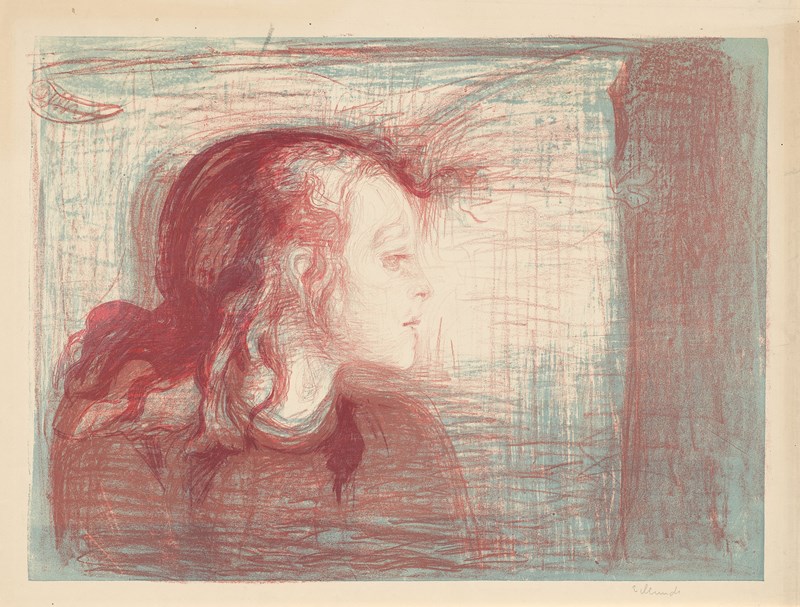

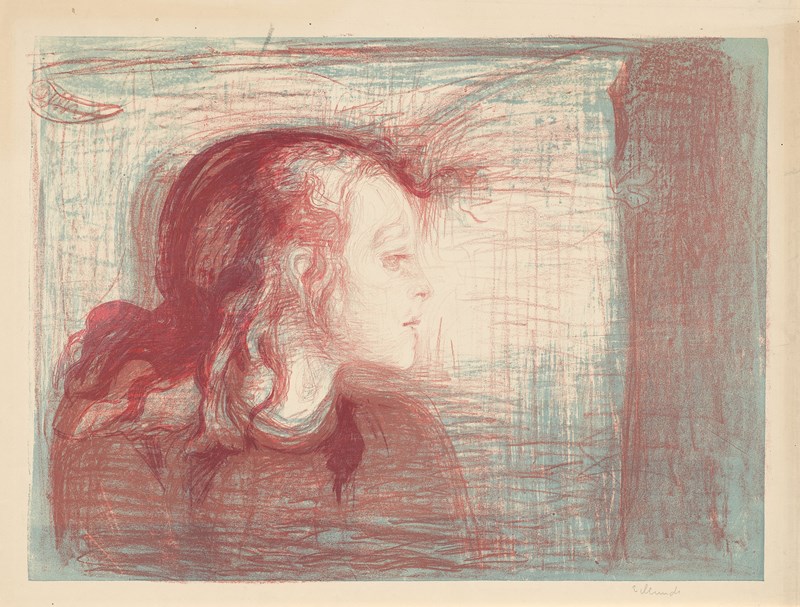

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child I. Lithograph, 1896. Photo © Munchmuseet

Edvard Munch exhibited the first painted version of The Sick Child at the Annual Autumn Exhibition in Kristiania (today Oslo) in 1886, when he was 23 years old. The coarse painting method was met with criticism by many, and enthusiasm from a select few, but the picture gained sufficient attention to mark Munch’s breakthrough as an artist. For Munch personally, it became a pivotal motif in his oeuvre. ‘With the sick child I broke new ground – it was a breakthrough in my art’, he later wrote of the motif. ‘Most of what I have done since had its genesis in this picture.’

Sophies sickness – one of Munchs most repeated motifs

The motif of the sick adolescent girl is based on Edvard Munch’s memories of his sister Sophie, who suffered from tuberculosis and died at the age of 15. Tuberculosis was a constant threat, both in society and in Munch’s family, and there was no cure – his mother died of the disease when the artist was five years old.

See also: A timeline of Munchs life

Munch painted the first version of The Sick Child in 1885–86, and according to his notes he worked on it for a long time. He wanted to reproduce his impression of his dying sister – her pallid complexion and reddish hair against the white pillow. He tried to express something that was difficult to capture; the tired movement of the eyelids, the lips that seem to whisper, the little flicker of life that remains.

See also: How Edvard Munch portrayed his childhood

This painted version of The Sick Child in MUNCHs collection, signed and dated 1926, was probably his sixth and last.

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child. Oil on canvas, 1927. Photo © Munchmuseet

The painting’s surface is characterized by a feverish creative process. Munch used a palette knife to scrape the paint and paint over it. The deep vertical and horizontal traces in the surface testify to the fact that he was in a state of inner turmoil, as though he wished to eradicate his sister’s death. There are six painted versions of the motif, made over several decades, from the 1880s to the late 1920s. Munch most likely felt that he had not succeeded in covering all the different aspects of his memory of his dying sister in one picture. He thought that the colours in the first version were not vivid enough, too grey, ’heavy as lead’, yet it is undoubtedly here that the sensitively rendered grief resonates most strongly. The composition is the same in all of the paintings, stripped of unnecessary details. The later versions are more colourful and all of them differ slightly – each contributed to enhance Munch’s memory.

Graphic versions

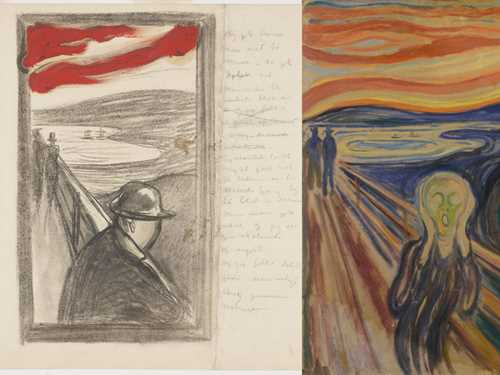

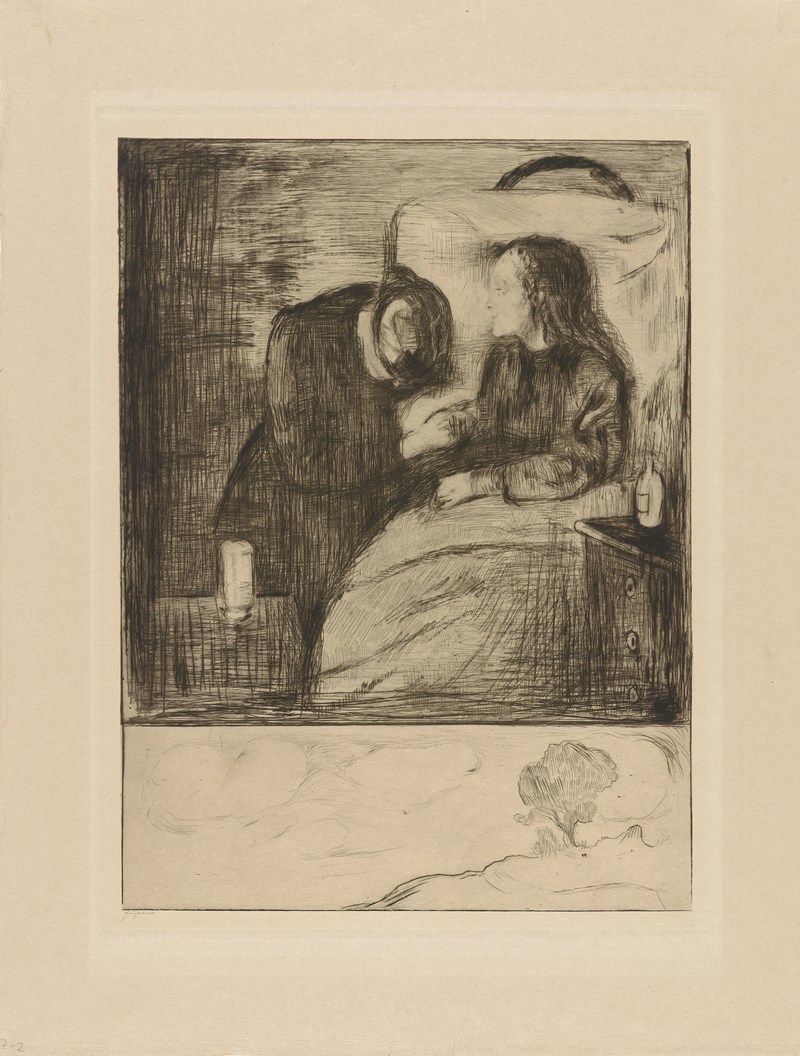

A few years later, when Munch started making prints, he quickly produced printed versions of the motif. First among them was the etched version from 1894. Munch added a miniature landscape underneath the motif itself, perhaps an allusion to what the sick girl is gazing at through the window, and pines after.

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child. Drypoint, 1894. Photo © Munchmuseet

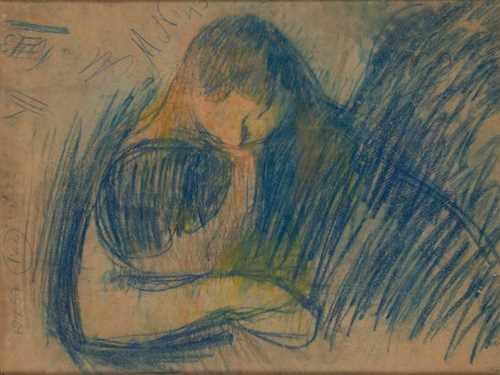

The most famous graphic version of the motif is nevertheless the lithograph. Unlike the painting and the etching, the lithograph focuses on the girl’s head, which Munch depicts with great sensitivity and empathy. The crude scraping on the stone gives the lithograph some of the same textured quality as the first painting.

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child I. Lithograph, 1896. Photo © Munchmuseet

The many variously coloured impressions pulled from this lithograph demonstrate how important the motif was to Munch. In lithography, each colour must be printed from a separate stone, and here he has drawn the motif, or parts of the motif, on as many as six stones. Each of them is then coated with different colours and printed in various combinations. This results in a wide range of colour renditions, with a correspondingly large register of expressions. In many examples, the colour red in different shades is dominant and creates an impression of the ravages caused by fever. The face remains pallid nevertheless, as a harbinger of what lies ahead.

Consolation is an element in both the painting and the etching, as expressed by the bowed woman who rests her hand on the girl’s arm. In the lithograph the sick child is alone, but in a couple of renditions Munch painted in the older woman’s face after the lithograph was printed.

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child I. Hand-coloured lithograph 1896. Photo © Munchmuseet

The skull-shaped head might not bring much solace, but it creates a human relationship in the picture just the same. Although Munch’s motif is rooted in personal memory, the many versions of it express a universal feeling of grief.

This text is based on excerpts from the collection catalogue "Munch Infinite" which will be published in 2021.