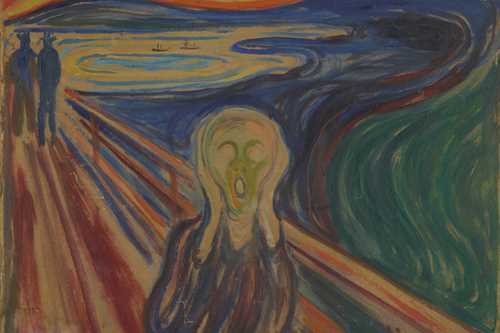

Munch paintings the world rejected

Did you know that several of Edvard Munch’s paintings were criticized and disliked in his own time? Or that some people who commissioned his paintings were so dissatisfied that they sent them back? Here are five paintings by Munch that shocked and provoked.

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child. Oil on canvas, 1925. Photo: Munchmuseet

A rejection by a friend

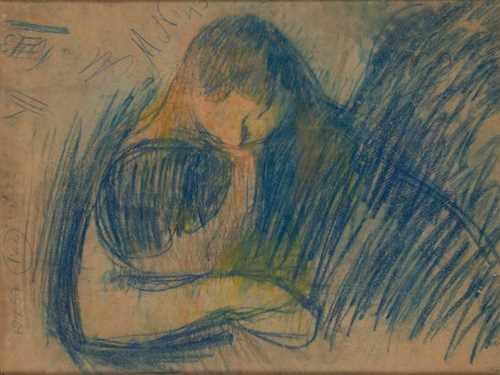

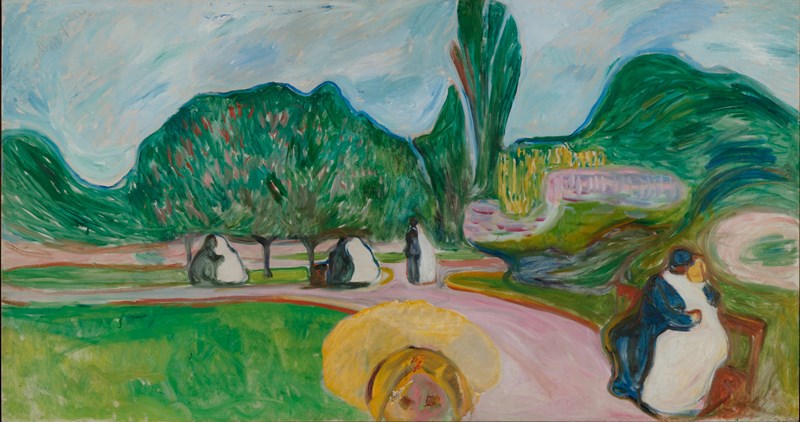

Max Linde, a wealthy physician and art collector who was a friend of Munch, commissioned a series of paintings for the children’s room in his home. Munch immediately came up with the idea of painting a summer scene set in a park. In Studenterlunden in the centre of Oslo he found young people kissing and embracing on park benches. His plan was to create a series of artworks about youth and early explorations of love.

When Max Linde saw the paintings, later called The Linde Frieze, they were not what he had expected. Not only were they full of erotically charged motifs, but the colours clashed with the French-style interiors of the children’s room. Linde’s rejection of the paintings was a major artistic and financial blow for Munch. Linde felt guilty about the rejection and offered to make up the financial loss by buying a version of one of Munch’s less controversial paintings.

You should be so kind as to keep to childish subjects, by which I mean in keeping with the nature of a child. In other words, no people kissing or making love, please. Because a child is completely ignorant of such things.

Edvard Munch: Kissing Couples in the Park (The Linde Frieze). Oil on canvas, 1904. Photo © Munchmuseet

Notoriety in Berlin

In 1892, the Association of Berlin Artists invited Munch to hold a major solo exhibition, which included the paintings Vision and Eroticism on a Summer Evening. The first reactions came the day after the official opening. The main problem, according to the critics, was that the paintings were unfinished: Munch must have brushed them onto the canvases at breakneck speed, thus showing arrogance, laziness and contempt, both for the general public and the art of painting itself. Twenty-three of the Association’s members demanded that the exhibition should be terminated “out of reverence for art”. At a general meeting, 120 members voted in favour of terminating the exhibition, while 105 voted against. Approximately 80 members walked in protest because they thought it was an outrage to turn away an invited guest. Munch soon managed to turn the scandal to his advantage, sending his notorious exhibition on a very profitable tour to seven other venues in Germany.

As this study is now, it is merely a discarded sketch, [the paint] half scraped off. He has become tired himself while working on it.”

What have you done to my wife?

Edvard Munch kept most of his paintings for himself. This also gave him great freedom to experiment. Even so, he sometimes accepted commissions, as in the summer of 1918, when the industrialist Wilhelm Mustad asked Munch to paint a portrait of his wife, Else. When Mustad took delivery of the painting, however, he was disappointed. He didn’t even recognize his wife! To Mustad, Else was an energetic, vivacious woman. Here she simply looked miserable. Subsequently, Else’s expression has been explained as reflecting the discomfort she experienced in modelling because she was suffering from the early stages of arthritis. Munch himself set great store by the painting, however, as was clear from his decision to exhibit it at Blomqvist the following year. When it was exhibited in Gothenburg in 1923, as part of an exhibition of Nordic art, it was described as a “painterly celebration of womanhood and youth”.

Provocative brush strokes

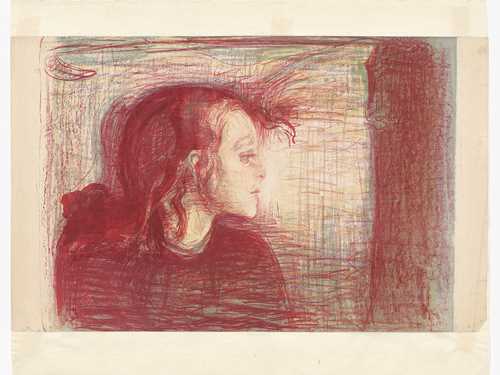

When Munch was 14 years old, his elder sister Sophie died of tuberculosis. Munch never forgot this experience, and it was a subject he would return to for the rest of his life. He first painted Sophie’s death in 1885. His model was a sickly young girl, who was one of his father’s patients. The painting was not only selected for the prestigious Autumn Exhibition in Norway in 1886, but it was even hung in a prominent position near the entrance. Several critics were harsh in their reviews of the painting. In their opinion, Munch damaged his own work with his technique. Others were more positive; pointing out that when the painting was viewed from a distance, the sensation of grief and pain that emerged made it a great work of art. The Sick Child represented a breakthrough for Munch, and today it is one of his most famous paintings. Munch returned to this motif several times during his lifetime, as he did with many of his paintings. He painted this version when he was 62 years old.

As this study is now, it is merely a discarded sketch, [the paint] half scraped off. He has become tired himself while working on it.”

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child. Oil on canvas, 1925. Photo: Munchmuseet

A monumental battle

In anticipation of the centenary of the University of Oslo in 1911, a competition was announced to create murals for the newly built ceremonial hall, the Aula. Many of Norway’s leading artists were invited to participate, but not Munch. He nevertheless got news of the competition, announced his interest by letter and was eventually allowed to join in. Finally, the choice stood between Munch and the painter Emmanuel Vigeland, but the jury remained deadlocked. They eventually put the competition on ice. But Munch kept going. He created smaller-scale versions of his Aula paintings, which he had exhibited in Germany to great acclaim. He was also allowed to exhibit his paintings on a temporary basis in the Aula. In the end a group of Munch’s supporters raised enough money to buy the paintings directly from Munch and donate them to the University of Kristiania. By then Munch had created hundreds of sketches, drafts and versions of the murals.