An interpretation of Edvard Munch's Vampire

From February-August 2023, an extensive and unique restoration process will be carried out for Vampire, painted in 1893. During this period the museum's painting conservator Eva Storevik Tveit reflects on Munch's well-known motif and puts it in a cultural-historical context.

Edvard Munch: Vampire. Oil on canvas, 1893. Photo: Munchmuseet.

Red hair envelops two bodies. Her arm tightens around both of them. Two bodies become one body. His face is barely visible as a pale profile, and his body is bent into her embrace, wrapped in her hair and floating into the blue background. Edvard Munch first titled the picture Love and Pain. Is the woman kissing the man on the neck? Or is she sucking his blood?

Edvard wrote about the painting:

"And he laid his head against her breast, felt the blood rush through her veins. He listened to her heart. And when he hid his face in her breast he feøt two burning lips to his neckc-it sent a shudder through him."

Edvard's friend Stanisław Przybyszewski said: "A broken man with a biting vampire face on his neck." He wrote: "In any case, he won't get rid of the vampire, he won't get rid of the pain either, and the woman will always sit there and will always bite with a thousand snake tongues, with a thousand poisonous teeth."

And just like that, Munch chose to change the title to Vampire.

In the novel I, Vampire, by Jody Scott, Sterling asks O'blivion's lover, Benaroya, an alien resembling a huge fish currently disguised as Virginia Woolf: "What is a Vampire? Who projected that image into you?"

Bohemian revolt against the established

In Munch's time, love often meant marriage, which in many ways represented the bohemians' fear of being engulfed in mediocre bourgeois life. They were critical of the established and of social conventional truths. When Edvard's painting Evening on Karl Johan (1892) was exhibited, critics questioned his mental health. The people in the painting are portrayed as enemies. They seem anemic and terrified and have rotted together into a large clan with the lights from the windows of the Norwegian Parliment behind them and a rebellious blue sky above them, on the sidelines a tree that resembles a large precipitous unclimbable mountain.

Edvard Munch, Evening on Karl Johan, 1892. Oil on unprimed canvas. Photo © Munchmuseet

Such a representation of the painting may coincide with the attitudes towards the established that were widespread in Edvard’s mileu, and attitudes of the bourgeoisie from which they tried to distance themselves.

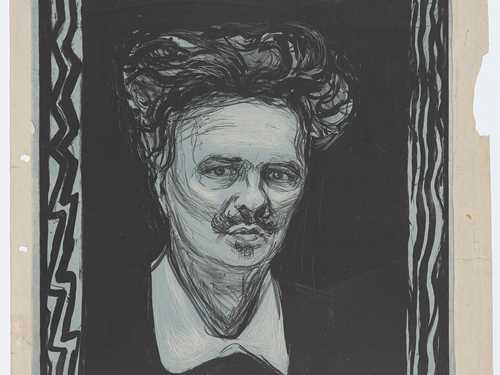

In 1893, Edvard took Dagny Juel to this bohemian mileu in Berlin and the bar Zum Schwarzen Ferkel, where they both became friends with, among others, the writers August Strindberg and Stanisław Przybyszewski.

Stanisław was an ardent bohemian and self-proclaimed Satanist, and his writings are filled with erotica and occultism. August had by this time written some of his best-known work. In the play Miss Julie and in the novel The Red Room, he questioned the moral norms and class and power structures of the time. He wrote: "One should paint one's inner life and not draw from logs and stones, which are meaningless in themselves (...)."

Two years later, Edvard said:

“No longer shall interiors and people reading

and women knitting be painted.

There shall be living people there

breathing and feeling, suffering and loving”

Although the environment around Stanisław, August and Edvard can be characterized as a slightly neurotic male-driven and anti-feminist, Dagny nevertheless gained access. She was perceived as innocent, similar to a liberated Madonna, although she was also described as vampire-like. She is probably the inspiration behind Edvard's painting Madonna (1893). "A Madonna's pale beauty. She experiences the moment when new life rushes through her, when the chain is tied to thousands of years back. Life is born to be born again and to die ...", he wrote.

Edvard Munch: Madonna. Oil on canvas, 1894. Photo © Munchmuseet

August called Dagny Aspasia, after the influential courtesan of ancient Greece. He feared that female liberation meant his unfreedom and Stanisław said things like: sexuality is a demon and in it man is helpless.

The Dangerous, Threatening Love

In myth and folklore, the vampire is a dead person who returns and feeds on the blood of the living. Vampires are not ghosts, not demons, but have characteristics of both. The devil is without a body, the vampire has a physical body of its own.

The fear of being weakened and drained, mercilessly used by a vampire is relatively anxiety-inducing. The man who loses control of his own behavior and destiny is a common scenario in the horror genre, the man who loses his energy. The painting Vampire thus expresses anxiety, a man consumed in a woman's embrace. Stanisław wrote about the painting: “A man broken in spirit; in the neck, the face of a biting vampire. The background – a wonderful mixture of blue, violet and green, 49 yellow dots, mixed together, floating together, next to each other like little crystal shards.”

In the engulfing embrace of a vampire, the man loses control, his power over himself, his energy and his reason as love or passion becomes all-consuming, removes peace of mind and ability to concentrate, freedom, independence and creativity, a dream that turns into a nightmare.

For Edvard, art eventually became more important than anything else. Rolf Stenersen wrote: "Munch fled from life and people by enclosing himself with his work, his art." He didn't want to get married. Stenersen further wrote that if Edvard fell into a relationship, he quickly rowed ashore. Edvard believed that women lived off men, and he compared them to leeches, dangerous predators. According to Stenersen, Edvard believed that women were beings with wings that sucked blood from their helpless victims.

Vampires drain the blood from the victim's veins, leaving them pale and powerless. In Vampire, the red-haired woman is the bloodsucker, the one who empties the man of creative power.

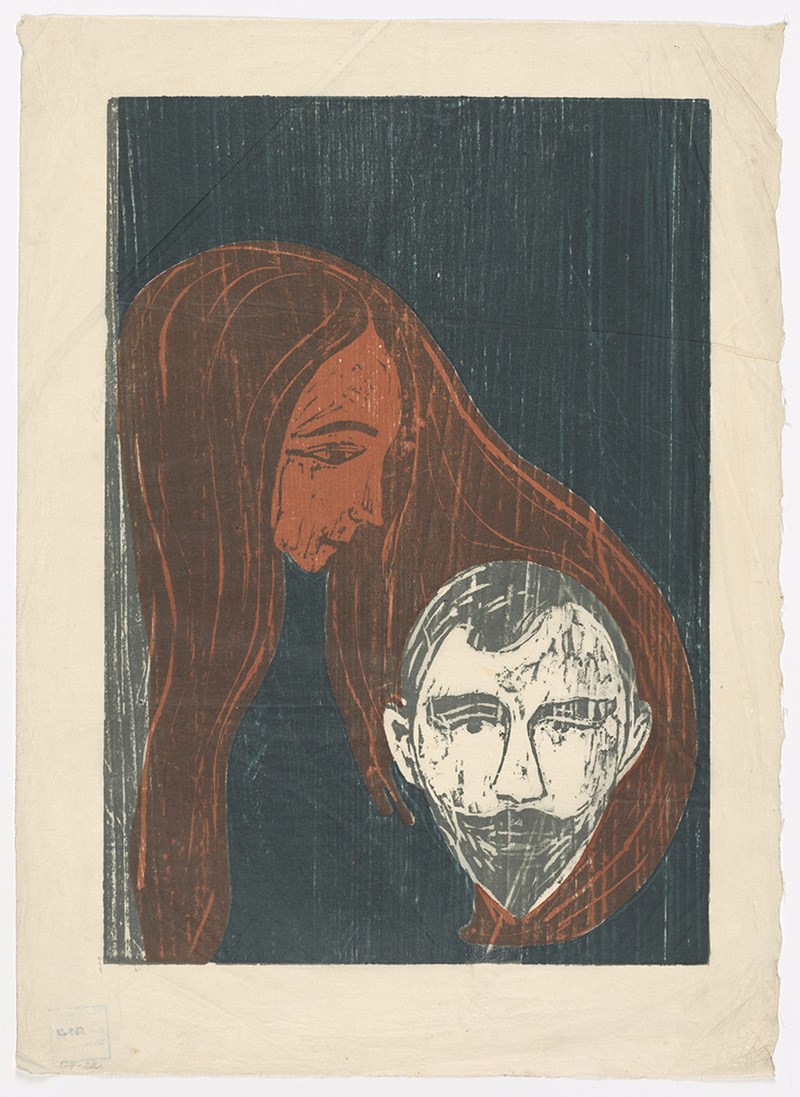

Edvard Munch, Man's Head in Woman's Hair, 1896. Colour woodcut. Photo © Munchmuseet

In Munch's time, the notion of the femme fatale was often linked with red hair. There is a Norwegian proverb that says: "Red hair and pine trees do not grow in good soil". Edvard portrayed women with red hair in several works, not only in Vampire, but also, for example, in the woodcut Man's Head in Woman's Hair, where the man is almost decapitated by the woman's red hair wrapped around his head.

Learn more about Munch's symbolic use of hair

In The Death of Marat, a motif Munch painted several versions of, the red-haired woman stands naked in front of the bed with the dead man in it and blood on the sheets.

Edvard Munch: The Death of Marat (1907). Oil on canvas, 153 × 149 cm. © Munchmuseet

It is well known that red symbolizes vitality, associated with blood and fire. August wrote about Vampire something like golden rain falling on a despairing figure who kneels before his lousy self and begs to be stabbed to death with her hairpins. It is claimed that the Neanderthals painted their dead bodies red to enable rebirth to Earth. In John's Revelation, the harlot in Babylon wore red. In that way, red became associated with the devil and hell. The Red-Light District is the name of the prostitution area in Amsterdam and Blue-stockings has been a term for intellectual women for several hundred years, whereas feminists were called red-stockings, because the woman was supposed to be submissive to the man. And to emphasize the pattern: baby Jesus is most often dressed in blue, and the Virgin Mary in red, but that makes the symbolism a bit ambiguous, because what is the woman then? The woman is both the virgin, the temptress and the Great Mother and in addition she was associated with the Holy Spirit.

Female Vampires

Who became vampires? Those who were bitten themselves, it has been claimed since ancient times. In Romania, vampires were something you were born as, not something you became. In ancient Greece, especially those who had committed suicide were at risk of becoming vampires.

Vampires had an awakening in the early 19th century. John Keats (1795-1821) took a particular interest in female vampires, and wrote Lamia in 1819. Robert Graves writes in White Goddess that Lamia are women who seduced, enervated and sucked the blood of travellers. Lamia is a temptress, the snake in the grass. In Greek mythology, Lamia is a rather obscure figure. She was the beautiful daughter of a king in Libya, and was seduced by Zeus. There are several variations of this myth. Lamia eventually became a sort of fairy tale figure used by mothers and nannies to promote good behavior among children. In literature, she also appears as seductive, vampire-like and tempting to young handsome men. She was also depicted as a woman who would devour her husband after he has agreed to marry, as described in Keats' story Lamia, a kind of femme fatale metaphor.

Left: Photo portrait of Dagny Juel, 1884. Right: Edvard Munch: Dagny Juel Przybyszewska, 1893. Oil on canvas, 1893. Photo © Munchmuseet

Was Dagny a Lamia of some sort? When she was alive, she was labeled as promiscuous, among other things. She was an independent woman, a hulder, which is a seductive forest creature from Scandinavian folklore, yes, a demon, some would say. Shrouded in myth, and Edvard's friend, but she married Stanisław. An Aspasia, as August said, Pericles' mistress and Socrates' friend, a woman who influenced and seduced men. August allegedly also had a relationship with Dagny, and according to Ketil Bjørnstad's The Story of Edvard Munch, the famous Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland threw a bust of Dagny out the window in an attempt to kill her.

Selene is another figure from Greek mythology, she is a goddess of the moon. Before she was a goddess, she was a human who worked as a housekeeper in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She worshiped Apollo, the Sun God, until he condemned her love for Ambrogio, who somehow became a vampire because when Selene was dying, Ambrogio drank her blood.

In the same year that Keats wrote Lamia, John William Polidori wrote The Vampyre in a competition where Mary Shelley produced Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. Publications that have inspired countless generations of vampire storytellers.

The Rise of the Vampire in Cultural History

In 1823, a few years after Keats' death, a law was introduced in England that forbade putting a stake through the heart of those who committed suicide. Not so many decades later, in 1872, the first lesbian vampire is introduced in Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu's novel Carmilla. In the novel Dracula from 1897, Bram Stoker (1847-1912) manages to show the anxiety in society at the time. This was not so long after Munch painted Vampire. And perhaps some of that anxiety is visible in Vampire, albeit on a more personal level. Dracula in many ways formed the basis of modern vampire fiction. At this time, as throughout the Victorian period (1837-1901), morality, hierarchy and the Bible were questioned. These values were no longer set in stone and many people gradually took a more liberal view, as the bohemians rebelled against traditional norms and the gender morality of the time.

God is dead, as Friedrich Nietzsche claimed, and man must create himself and his own values. Shaking such authorities and societal governing elements, and opening up the individual's own freedom, created anxiety.

Edvard Munch: Friedrich Nietzsche. Oil and tempera on canvas, 1906. Photo © Munchmuseet

In the introduction to the 1993 edition of Dracula, David Rogers writes that anxiety characterized the patriarchal late-Victorian era. Into this scene comes Dracula and threatens the established order. Some also argue that there is an erotic aspect to the blood drinking in Dracula, such as when Dracula transforms Lucy Westenra into a sensual seductress. And perhaps those were the thoughts Stanisław had when he compared sexuality to a demon. Actor Louis, who played Dracula in the BBC's 1977 Count Dracula, said that making love is like a pale shadow of killing. Drinking blood washes away the distinction between one's body and the other's body. Louis compares the blood sucking to the memory of sucking milk from his mother's breast.

Vampires have changed over the years. Vampires today are portrayed as slaying monsters with passionate personalities, romantic and tormented. Before 1980, the vampire conceptions often corresponded to Stoker's Dracula and Eastern European folklore. After the 80s, we have met other types of vampires in popular culture, like the ones in the Fright Night movies.

In 1924-25 Edvard paints his final vampire motif, Vampire in the forest. Here the woman and the man are naked, surrounded by dense forest. They almost appear as an integrated part of nature. A few years later, when Edvard is in his mid-50s, he reflects on the relationship between women and men in his time, and writes the following in 1929: "I have lived in my transition period in women's emancipation. Then it became the woman who seduces and entices and deceives the man [...] In the transition period, the man became the weaker one."

From 28 October, the newly restored Vampire will be on display in the exhibition Goya and Munch: Modern Prophecies.

Read more about the significant restoration process the painting has been through, with support from Bank of America.

![Edvard Munch: [Title under consideration]. Oil on canvas, 1916. Photo © Munchmuseet](/globalassets/kunstverk/tittel-til-vurdreing.jpg?w=500&h=375&mode=Crop&quality=50&crop=0,417,2154,2032)