Between us and the Sun

The Sun is one of Edvard Munch’s most famous works. But what does a sunrise over the rocky Norwegian coast have to do with well-toned physiques and the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche?

Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1910–11. Oil on canvas. Photo © Munchmuseet.

“The sun has been roasting hot all day, and we let it roast [us]. Munch has done a bit of work on a swimming painting, but for most of day we were lying around, overwhelmed by the sun, in deep sand dunes right down by the edge of the fjord, between the big boulders, and letting our bodies drink up all the sun they could bear. No one is bothered about swimming costumes here, the gentle gusts of a warm July wind are the only fabric between us the sun.”

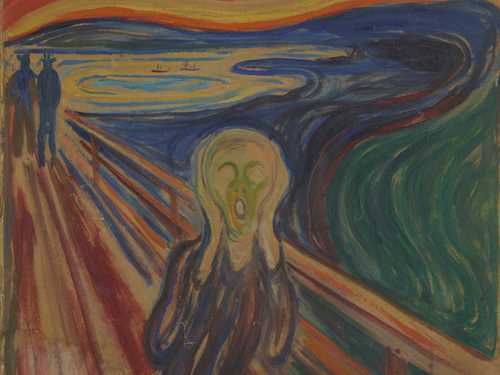

This is how Christian Gierløff, a close friend of Edvard Munch, described some scorching summer days he shared with the artist in 1904. One can almost feel the life-giving force of the sunbeams on one’s body when reading his words. One may have a similar experience when encountering Munch’s monumental masterpiece The Sun, which depicts a glowing sunrise over the rocky archipelago off Kragerø.

A special life force

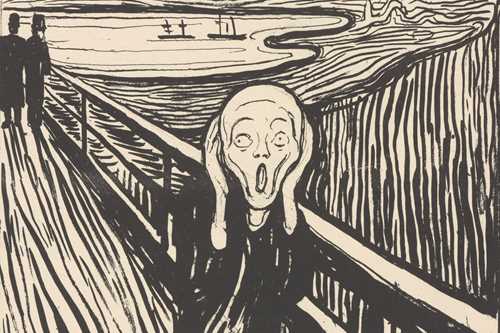

This famous image was created for the University of Oslo’s new ceremonial hall (Aula), which had been built in connection with the University’s centenary celebrations in 1911. This was Munch’s first major commission for a public institution, and he worked on the prestigious project for many years, during which he made several hundred preparatory drawings and paintings. The MUNCH collection has several versions of The Sun, including a full-size preparatory oil sketch that Munch painted in 1910–11.

The Sun is one of 11 large paintings created for the walls of the Aula. Located on the end wall, it depicts sunbeams radiating out towards the panels on either side, where naked men and women reach up towards the light. Among other things, these images reflect Munch’s interest in nature and Vitalism, a school of scientific thought that promoted health, hygiene and physical education, and that emphasized the sun as an energy-giving force.

The Aula, The University of Oslo. Alma Mater is on the right hand and the Sun in the centre. Photo: Jaro Hollan © Munchmuseet

The influence of Vitalism extended into most areas of society, from sport and physical culture to philosophy, literature and the visual arts. The term derives from the Latin word vitalis, which means “of or belonging to life”, and the movement was based on the idea that all living organisms have a special living, or vital, force.

Primitive man

Vitalism is often seen as a reaction to the fin-de-siècle decadence of the 1890s, as well as to urbanization, pollution and decay. The new ideal human was healthly, enthusiastic, strong, and naked. There was widespread nostalgia for the lifestyles of primitive humans, at one with nature.

One important source of inspiration for Vitalism was the thinking of the German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche. His book Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in which the cleansing power of the sun is one of the central themes, was particularly influential. Nietzsche – whom Munch admired and of whom he painted a posthumous portrait in 1906 – criticized the decadence of contemporary culture and morality and was preoccupied with notions about primitive man.

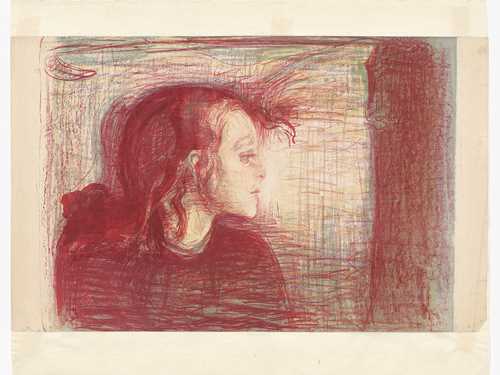

Edvard Munch: Friedrich Nietzsche. Oil and tempera on canvas, 1906. Photo © Munchmuseet

The many aspects of the Sun

All of Munch’s images have an element of ambiguity, and perhaps this is why they never cease to fascinate us. As depicted by Munch, the sun can be understood as a symbol of the eternal and universal, while at the same time its brightly coloured beams remind us of what was then ground-breaking scientific research into x-rays, magnetism and the Northern Lights. For many of us, this image awakens memories of sunlit mornings by the sea.

Munch himself described its origins in two short sentences:

“I saw the sun rise up above the cliffs – I painted the sun.”

The Sun can be experienced up close in the exhibition Edvard Munch Monumental, on floor 6 at MUNCH.

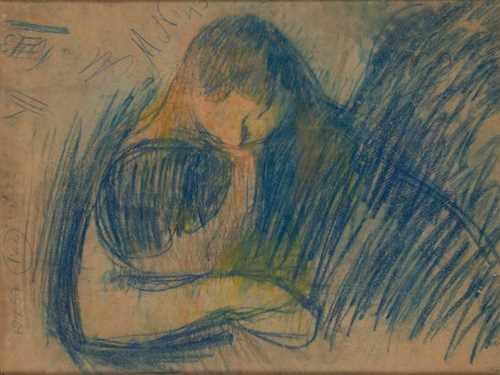

![Edvard Munch: [Title under consideration]. Oil on canvas, 1916. Photo © Munchmuseet](/globalassets/kunstverk/tittel-til-vurdreing.jpg?w=500&h=375&mode=Crop&quality=50&crop=0,417,2154,2032)