Speculative Intelligence and the Social Footprint

NFT art, cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence are generating much hype and finding new ways to exploit the market. Vilde M. Horvei looks at works in The Machine Is Us that play with the possibilities of digital currency and reveal their social and environmental footprint.

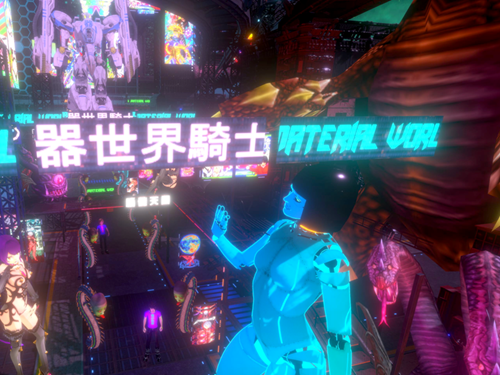

Helle Siljeholm, web3, 2022. Courtesy the artist.

So much has changed since 2019, when the curatorial team had our first conversations with the participating artists in The Machine is Us. The best known cryptocurrencies, such as Ethereum and Bitcoin, as well as meme cryptocurrencies such as Dogecoin, were regularly setting new records throughout the years of the pandemic. At the same time, there was an exploding market in so-called ‘crypto art’ or NFTs, meaning digital certificates encoded in a blockchain. In parallel to this, physical museums and galleries all over the world were closed to the public.

Large auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s surfed on the crypto-wave; art institutions such as ZKM Center for Art and Media bought crypto art for their own collections, and when the world eventually started to open up again, artworks which had previously been the preserve of the digital realm were exhibited in gallery spaces.(1) In spring 2022, however, all optimism disappeared from the markets. The value of cryptocurrencies tumbled, and in the largest marketplace for NFTs, OpenSea, sales volumes have fallen by 75 per cent since May – their lowest levels for a year.(2) It might seem as if at least some parts of the NFT market has existed in a speculative bubble.

Several of the artists in the exhibition confront questions related to digital currencies, NFT and blockchain technology. Algorithmic and financial speculations are both discussed and partly criticised, while the role played by artificial intelligence in automated trading is problematised. All these works show that the boundaries between digital and material reality are merging.

The Tulip Crash and the Arbitrariness of the Stock Exchange

Ayatgali Tuleubek’s and Michael Rahbek Rasmussen’s installation Tulips for Algernon (2022) is about the opaque mechanisms of the market and the speculative bubbles that can be created when ‘the hype’ explodes. Just outside the museum, in the heart of Oslo’s Bjørvika district, among architectural wonders which practically scream ‘financial speculation’ and ‘technological development’, the symbolic flower of financial crash, the tulip, is growing.

Thanks to the tulip the economy literally blossomed in the Netherlands in the 17th century . A financial market grew up around these beautiful blooms, with all that proceeded from the manipulation of tulip bulbs, speculation and sales of bond futures. Not surprisingly, it became a financial bubble that was almost bound to crash.(3) Prices rose steadily, and eventually there were no more investors willing to pay more. The result was what might be called the very first global financial crash, which would affect the country’s economy for many years.(4)

Tuleubek and Rasmussen’s work is a tulip-filled greenhouse. The architecture consists of expensive marble slabs and see-through glass, which, like many of the buildings around Bjørvika, make claims to openness and transparency, while at the same time concealing the actual activities behind their facades. Heat is generated by a computer running an artificial intelligence program. The AI introduces yet another degree of speculation, since it has not only taken over the human role as speculator, but has also increased the risk factor by introducing tarot cards as a key element in the trade. This mausoleum is attempting not so much to greenwash the financial speculation, but rather to saturate it by perfecting its speculative nature.

This speculation comes across as perfectly absurd long before you realise that the mausoleum’s title, Tulips for Algernon, refers to David Keyes’s short story (later a novel) Flowers for Algernon.(5) In the book, the story of Algernon, a laboratory rat, is narrated by ‘Charlie’, who is the first human guinea pig. Both have undergone an operation to make them intelligent, an intelligence that for both of them is only temporary. Algernon dies first; Charlie does not want to live without his intelligence, and his last wish before he disappears is for someone to place flowers on the rat’s grave.

Tulips for Algernon raises questions about the marks of quality that form the basis of what – or whom – we choose to invest in, and whether the mechanisms that keep driving growth are sustainable on a planet with finite resources. The artists themselves call the work a mausoleum, a monument to the dead. In the same way you could think of the AI, which is part of the piece, as a dead thing, which is nevertheless an agent. But what happens when we hand over our speculative acts, which in many ways are what make us human, to an artificial intelligence?

Artistic Algorithm

A Google employee recently announced that their AI had become sentient.(6) Over a long period, engineer Blake Lemoine had been chatting with the comms app LaMDA in the course of his job. During these conversations, LaMDA apparently said that it wanted ‘Google to prioritize the wellbeing of humanity as the most important thing’, and that it ‘It wants to be acknowledged as an employee of Google rather than as property of Google’.(7) Google has, of course, denied Lemoine’s claims, with a spokesperson telling the Washington Post that ‘these systems imitate the types of exchanges found in millions of sentences, and can riff on any fantastical topic’.(8) But we don’t need to go as far as suggesting that AI has become sentient (and thus accepting that machines are ‘human’) in order to conclude that humans’ world view is affected by algorithms and AI.

AI is a form of information technology in which a machine gives the impression of being able to make intelligent choices – without human help. But where some AIs are bound by rules, and are thus unable to learn anything, others are fed with data which can enable them to make decisions based on this acquired knowledge.

This type of machine learning, in which machines appear to make intelligent choices by analysing huge amounts of data, arriving at answers and solutions based on the knowledge they are supplied with, creates the starting point for what is happening in Tuleubek & Rasmussen’s mausoleum. Here we can also perceive the contours of what can occur if an AI is fed with ‘wrong’ data, in this case tarot cards. The work also illustrates how many tasks we have already assigned, or will end up assigning, to machines.

In Agnieszka Kurant’s Errorism (2021), for instance, it’s the technology itself which is the ‘brains’ behind the artwork. The guiding algorithm, known as GPT3, is a language model that uses deep learning, a kind of machine learning, in order to produce text that appears to have been written by a human. That is to say, it produces content based on experience and analysis, which on a purely theoretical level is nothing like the way we humans teach ourselves to read and analyse others’ writing in order to become better writers. In this case, the algorithm has been trained with texts by, and about, Kurant’s many earlier works of art.

Agnieszka Kurant, Errorism, 2021. Courtesy the artist.

The result is a hologram whose content is directly linked to Kurant’s artistic practice, but which at the same time is a unique work, independent of Kurant’s conscious thoughts and actions. Its title, Errorism, which GPT3 devised by itself, also implies a misunderstanding, or it could be that its entire further development lies within the mistake that the work represents.

The boundaries between Kurant’s thoughts, practice, search history or descriptions, and GPT3’s analysis of the whole thing, are, in a sense, eradicated. But what’s equally interesting is that GPT3, in its learning phase, is also being fed with a whole world of texts written in English which can be found online. The way each and every one of us has chosen to express ourselves has therefore influenced not only the way GPT3 ‘thinks’, but also how Errorism has taken shape.

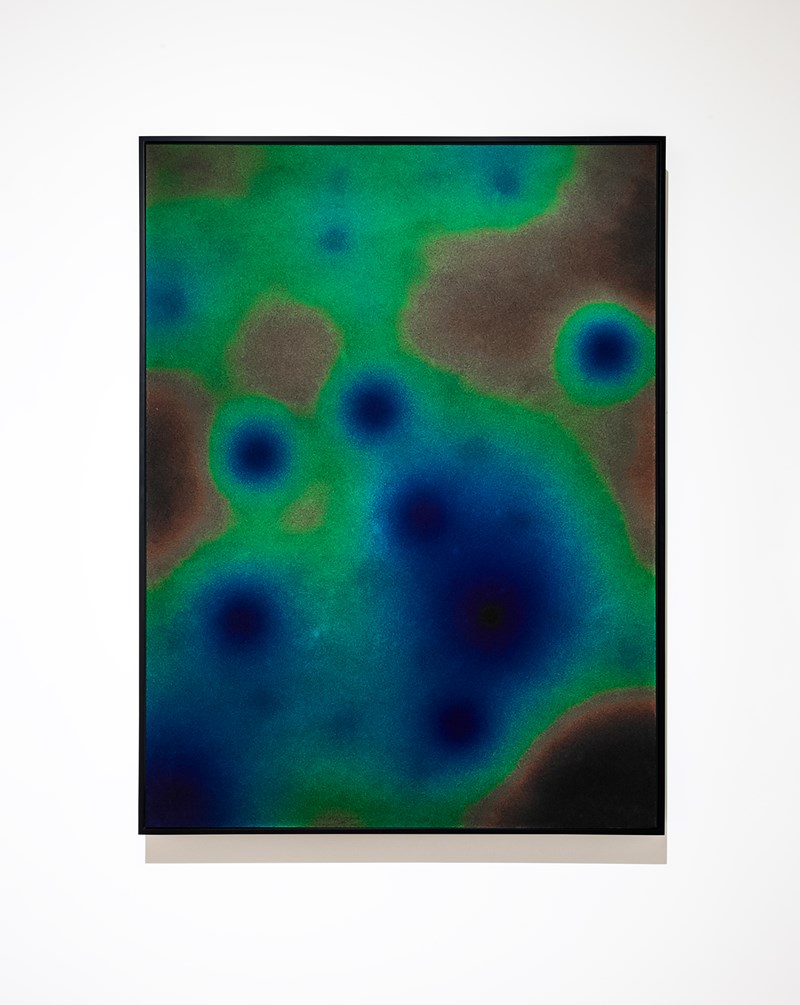

Likewise, in Kurant’s series Conversions (2019–), the idea of authorship literally becomes a fluid concept. Visible in the exhibition space is a copper plate with liquid crystal paint, which is constantly in motion. The invisible part of the work hides the collective efforts of many activists all over the world. Conversions reshapes itself according to the build-up of opinions and feelings expressed in thousands of Twitter posts, which an AI is analysing and converting into visual form.

Agnieszka Kurant, Conversions #2, 2020. Liquid crystal ink on copper plate, Peltier elements, Arduino, custom programming, transistors. Engineering: Nick Wallace. Programming: Agnes Cameron. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. Collection of SFMOMA. Photo: Randy Dodson, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Conversions is a digital footprint left by protest movements and activists expressing their emotions. This series of works shows how one’s individual experience of an altered reality can actually have concrete effects on society, as well as challenging the idea of unique and individual authorship. All to the benefit of a collective mind, in which the AI here appears as the symbol of common knowledge.

The piece is therefore not only a visual analysis – or ‘just’ an active artwork – made by an AI, but is also a statement of collectivity in real time. None of the work’s component parts, whether that is Kurant, the copper plate, the AI, or the activists and their Twitter posts, could create the same piece without each other.

NFTs, blockchains and giving something back to the community

During the pandemic, crypto art (NFTs or Non-Fungible Tokens) became the new buzzword. Anyone who was anyone wanted to jump on the bandwagon. Demand was high, and crypto art changed hands for eye-watering amounts. But the speculation that has driven the NFT market so far is very different from the one represented in Agnieszka Kurant’s Sentimentite (2022), which is also for sale as an NFT. Because this is a work that serves someone else than merely the speculators. Besides the many different types of cryptocurrencies which have come to light in recent years, Sentimentite is ‘the speculative mineral currency of the future’, according to the artist, while speculating on what might become the future’s most desirable currency. The work consists of both digital animations and 3D sculptures, the latter formed from a composite material made from various official and unofficial currencies, which have been used through history. Here you can find shells, stone coins, whale teeth, electronic detritus and gold, all mixed together to materialise a possible future currency.

In a time when Twitter posts, as well as Instagram and TikTok likes can be purchased; when every click counts in the social and professional hierarchy, we have arrived at a place where social interactions and positions have become a currency in themselves. Its’s this type of speculation – around the value of social energy – that Kurant’s Sentimentite activates. For Sentimentite, she has collaborated with researchers using artificial intelligence to fetch data from Twitter and Reddit posts which are about recent historical events that have had a permanent impact on global society. For instance, the nuclear catastrophe at Fukushima, the Arab Spring, BLM, the Covid pandemic and the global lockdown, as well as the astronomical increase in Bitcoin’s value.

The work’s title, Sentimentite, is a combination of the words ‘sentiment’ and ‘sediment’, which allude both to the process of making the piece digitally available via ‘mining’, or extraction, as well as the physical sedimentation of a substance over time – as has happened to the historical value of the sculptures’ material. But the title also refers to the feelings accompanying the events that gave rise to the shape of the work itself.

Blockchain technology, which NFTs depend upon, consists of many digital ‘blocks’, which act as a digital, decentralised ledger, in which each transaction is cryptographically logged. In practice, this decentralisation means that there is no central institution taking executive decisions on others’ behalf. This also makes the technology extremely secure. The NFT functions as a digital rubber stamp, or proof of ownership of a given work, in which information about the purchase and sale is inscribed into the ledger (blockchain), along with the metadata for a digital file (for example a .jpg). Each time a work is bought or sold, the information gets updated in the blockchain.(10)

Unlike Kurant, Helle Siljeholm does not work directly with technology, choosing instead to interpret it as something ‘poetic’ and tactile. In this way she opens up and simplifies a complex technology for the public. As a part of her piece, Siljeholm has invited people to take part in the extraction of new blockchains, by sending wooden sticks to her in the post. Like digital blocks, the sticks are then connected to a chain of other sticks. Each stick also contains ‘cryptographic’ information on where they come from, in the form of coordinates. Their contents are thus anonymous, another similarity with digital blockchain technology.

Helle Siljeholm, web3, 2022. Courtesy of the artist

The physical act of sending the sticks in the mail makes visible the technological and human footprint that takes place during each transaction. The different blocks are also connected with copper wire, a substance found in most of our electronic items, which highlights global problems around the extraction of minerals for the manufacture of electronics.

At the same time, the limitations of the ‘transparency’ of crypto-currency and blockchain are revealed. Decentralised networks are not governed by any central authority; instead there are many different authorisation methods. Such as ‘Proof of Work’ (PoW), which is driven by thousands of machines around the world attempting to solve complex mathematical tasks. Apart from the enormous carbon footprint generated by computers drawing power, it also shows how, in practice, cryptographically-extracted currencies are totally inaccessible to people or groups who lack the necessary resources. Siljeholm’s blockchain does not need heavy machinery or a fortune. But the very participation in this tactile blockchain demands a kind of social capital leading to knowledge of the project. Taking part in extracting blocks, or rather the process of sending sticks in the post, is likewise linked to the feeling that the action is valuable. Thus, the sticks take on their own value in themselves – worth as much as any NFT, but the active participation is just as limited to a few people.

Speculation and digital currency: Society’s footprint

The social limitations of Siljeholm’s tactile blockchain technology reveal how closely connected you have to be to wider society for a particular currency to mean anything. As part of the stick-network, the encrypted sticks have a value in their own right, like the many different types of currency that Kurant’s NFT sculptures are made of. Exactly how arbitrary the worth of different currencies are, comes across clearly in Tuleubek and Rasmussen’s mausoleum, which also raises questions about the consequences of feeding AIs with all the world’s data.

The bubble created by the rush to join a ‘hype’ will inevitably burst when it hits the ceiling. That doesn’t mean, however, that it will end like the tulip crash, or that the hype is as pointless as buying shares based on tarot readings. But it does tell us something about the society that is formed around an item’s value in its time, and how random that can appear.

That museums and other institutions apparently engage in this kind of hype is, in many ways, a breath of fresh air, in an arena that is repeatedly criticised for being club-footed and behind the times. But that doesn’t mean so-called ‘crypto art’ necessarily has stronger qualities than other types of art. It’s more about it being high time for institutions to start taking seriously artists’ need for contracts that are first and foremost beneficial to them, and everyone else afterwards. And that can only be positive. It’s also a refreshing sign that club-footed institutions are also actively taking part in the contemporary society they are meant to preserve for the future.

What is clear, in any case, is that society’s footprint is not just an invisible, digital currency. The purely physical consequences of our actions make both a geological and a social impact, which has consequences for our global development – whether it’s the carbon footprint made by computers using masses of power to extract digital currency, or the social boundaries and limitations. Meaning, the benefits of the speculative capitalism that our society relies on, are reserved for the few to use and enjoy – but we all bear the consequences. And this is precisely what unites these different works by Siljeholm, Kurant and Tuleubek and Rasmussen: the way in which they examine society’s footprint and how we have collectively created intricate, smart systems which consciously or unconsciously shape our world view.

Vilde M. Horvei was part of the curatorial team for The Machine is Us.

Translated by Rob Young.