Sandra Mujinga – towards an exhibition history

Senior Curator of Contemporary Art, Tominga O’Donnell, traces the roots of Sandra Mujinga’s new installation for MUNCH in the artist’s recent exhibitions.

Sandra Mujinga, installation view of Spectral Keepers at The Approach, London (2021). Photo by Lewis Ronald. Courtesy the artist and The Approach, London.

Elements from Mujinga’s previous works include the characteristic use of green light in combination with a darkened space, a three-part installation, oversized figures (speculative hybrid creatures that could have emerged from the deep seas or from an outer galaxy), opaque Plexiglas and blurred outlines that evade visual capture. At the same time, the commission for MUNCH points to some new tendencies in the work of this extraordinary artist and visionary thinker.

I had not read much science fiction before my first conversation with Sandra Mujinga in 2019, but I have found that following an artist’s literary recommendations offers a valuable point of entry to understanding their work. One author whose name kept coming up in our dialogue was N.K. Jemisin. In her book, The Fifth Season, an orogene is someone who can ‘sess’ earthquakes before they happen and use their extraordinary powers to absorb them, albeit at great physical cost. In a world devastated by natural disasters that usher in new ‘seasons’ the orogenes’ strength is their ability to sense beyond the sensible, to notice seismic shifts before they turn into catastrophes.

The figure of the orogene stayed with me as I tried to navigate Mujinga’s rich and complex exhibition history leading up to her commission for MUNCH. It was particularly present as I watched Mujinga’s performance, You Are All You Need, at her solo show at Bergen Kunsthall in 2019, in which two actors, Terese Mungai-Foyn and Mariama Ndure, ruminated on ‘mourning the event by having exhibitions’. As audience members, we were not explicitly told what this ‘event’ had been, but its meaning was alluded to as the actors repeated their introductions to what initially seemed like a conventional ‘artist talk’, stating their names, where they were based and the mediums they worked in, before gradually providing more information. There were references to volcanic soil, to panic, to lava, to an eruption. One of them added, ‘It could have been worse if we were next to the lake’. The actors’ deadpan delivery could not mask the ominous sense of a disaster – past but also present.

The story was located out of time and place. Ngogobeihli, where both artists were supposedly ‘based’, does not exist according to an internet search, although the name might be a reference to the Ngogo community of chimpanzees in Uganda. By resemblance, the ‘event’ could refer to Mount Nyiragongo, an active stratovolcano in the Democratic Republic of Congo, just north of Lake Kivu and the town of Goma, Sandra Mujinga’s place of birth. At the time of the performance, the volcano’s last eruption was in 2002. It erupted again in 2021, causing mass panic, as the citizens of Goma had to evacuate quickly to avoid the imminent threat of flowing lava.

Sandra Mujinga, Flo (2019). Installation view of Midnight at Vleeshal, Middelburg (2020) Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, and The Approach, London.

Opening at the end of 2019, Mujinga’s solo exhibition in Bergen, entitled SONW – Shadow of New Worlds, featured two new works by the artist, including the centrepiece Flo – a video hologram, named after the artist’s deceased mother. The eponymous character emerged, hovering in space, like some ethereal presence, before passing through a darkened corridor bisecting the largest gallery in the Kunsthall. The figure was outsized, a weightless giant with bulging muscles, draped in seagrass-like garments; the contours of its face and neck precisely drawn in profile in luminous green. ‘Flo’ might just as well have emerged from the depths below as the heavens above.

The second new work in the exhibition, Coiling, drew on Mujinga’s technique of combining artificial materials via their deconstruction: burnt acrylic paint, melted polyester and heat-treated PVC. Coiling resembled the tattered sails of a ghost ship or something found in the post-apocalyptic landscape of the mid-1980s sci-fi/action film Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome.

The exhibition in Bergen, billed as Mujinga’s largest solo show to date, also included Nocturnal Kinship (2018), originally exhibited as part of her solo display Calluses at Tranen, outside Copenhagen. Large, hooded figures, pleather costumes with reflective detailing, hovered in the central gallery of the Kunsthall, bathed in the green light that has become a hallmark of Mujinga’s installations.

Another work, Camouflage Waves 1–3 (2018), was previously shown at Tranen and in Mujinga’s exhibition Hoarse Globules at the Young Artists’ Society in Oslo. Here, standing figures – quite bulky as if dressed in oversized bomber jackets – were partially obscured from view by a semi-transparent covering made from inkjet print on film merged with soft PVC using heat. The degree of visibility varied, making it difficult to make out who or what was behind the surface layer, covered in viscous globs like raindrops on a windscreen. It generated a strong urge in me to wipe the screen, to uncover the hidden figure beneath or to reposition oneself so that the shape might emerge as human.

Sandra Mujinga, Nockturnal Kinship (2018), installation view of Calluses at Tranen. Courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen Vienna.

Sandra Mujinga, Camouflage Waves 1 (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen Vienna.

This denial of visibility runs through Mujinga’s practice. It evokes the writer Édouard Glissant’s concept of opacity, which he described in Poetics of Relation as a right one could demand: the right not to be understood. Drawing on his lived experience as a Martiniquan scholar based in France, Glissant formulated opacity as a strategy deployed against an expectation of transparency. It referred to the Other’s right to reject the scrutiny and any claim of full comprehension, especially from the West, though, as Glissant asserted, ‘we clamour for the right to opacity for everyone’.

At the opening of the 10th Berlin Biennale, entitled We Don’t Need Another Hero, curator Gabi Ngcobo referred to Glissant as she launched the graphic identity of the biennial with camouflage as its guiding motif, claiming the right to opacity both on behalf of the works in the exhibition and herself as its presumed spokesperson. In a similar way in Mujinga’s work, the opaque covering becomes the material manifestation of the titular camouflage. Another of the artist’s works, the video Disruptive Pattern (2018), evoked a different kind of concealment, namely homochromia, whereby creatures hide by changing their colour to that of their surroundings. In the video, the image travelling across the screen became fluid, its contours blurred, shifting in and out of focus in a manner similar to the figure behind the covering in Camouflage Waves 1–3, though now with colour and contrast as additional layers of confusion.

Sandra Mujinga, Lovely Hosts 1 (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen Vienna.

A less intentional form of obscuration could be found in Mujinga’s work, Lovely Hosts 1–7 (2016), initially shown at Mavra in Berlin. A computer virus disrupted digital photos the artist had taken while travelling across the city of Kisangani in the DRC. It was a glitch, causing pixelations that distorted the images and which the finished photoprint underscored with its perforations and eyelets, as though the paper had been peppered with multiple shots. In Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, Legacy Russell celebrates the glitch as ‘a vehicle of refusal, a strategy of non-performance’. By celebrating the mechanical error, even enhancing it, Mujinga harnessed the power of the glitch to open up new vistas of potential meaning in a partial landscape between the physical and the digital.

Sandra Mujinga, Stretched Delays 2 (2017). Photo by Tor Simen Ulstein. Courtesy of the artist, Croy Nielsen Vienna and The Approach, London.

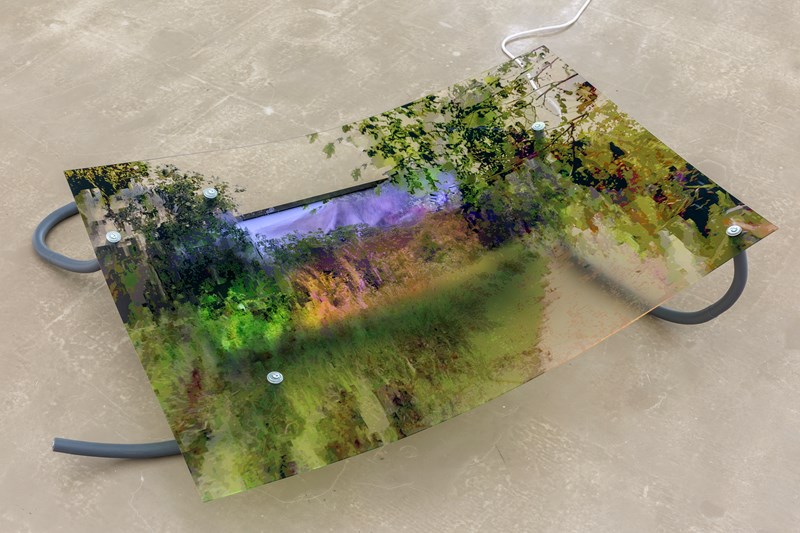

Stretched Delays 1–4 (2017), a work first shown at Kristiansand Kunsthall, was also included in the Bergen Kunsthall exhibition. Placed on the floor, the work consisted of four crus crab-like creatures with curving silicone-covered metal rods for legs and Plexiglas bodies, jealously guarding and blocking the view of LED screens below. The semi-transparent bodies had images printed them, reproducing stills from the screens beneath, making the performers exist in between. From a distance, the various shades of green and brown made it look like it had been dragged along the seabed. This interest in creating works resembling deep-sea creatures has been present in Mujinga’s practice from its inception, predating the recent documentary film My Octopus Teacher (2020) that has given this particular creature a larger pop-cultural following. In fact, the popularity of the octopus has a longer art-historical trajectory – from Hokusai’s 19th-century woodcuts to Jean Painlevé’s early and mid-20th-century films dedicated to cephalopods. In 2015, Mujinga created Scales. Pros and Cons. On Becoming a Sea Creature, which followed a mermaid-like figure underwater, blurred and blended with digital blobs, a mobile version of the static globules in Camouflage Waves. The octopus emerged as a sculptural form in the artist’s work at around the same time with Octo Hoodie/Backpack (2015), a shape that was adapted in Octo Handbag (2017) and in Octo Clutch/Temporary Home (2018).

Sandra Mujinga, Octo Clutch/Temporary Home (2018). Photo by Jan Søndergaard. Courtesy the artist and The Approach, London

It is not only the creatures of the sea that figure in Mujinga’s work, but also animals such as gorillas and elephants. In her solo exhibition, Real Friends, at Oslo Kunstforening in 2016, Mujinga included portraits of gorillas, Humans, on the Other Hand, Lied Easily and Often. In an on-going body of work from 2016, entitled Shawl (Elephant Ears), Mujinga used her characteristic mix of PVC, acrylic paint and glycerine to create textured sculptures reminiscent of the mammals’ large ears. With one side grotesquely flesh-like, it looked like the body part had been amputated, perhaps referencing the widespread poaching of elephants, where the removal of their tusks leaves a gaping, reddish-pink flesh wound on the otherwise grey-brown, thick-skinned animal.

Sandra Mujinga, Humans, On The Other Hand, Lied Easily and Often 1 (2016). Photo by Ink Agop. Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, and The Approach, London

Sandra Mujinga, Shawl (Elephant Ears), 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

This evident empathy with animals in Mujinga’s work reminds me of Donna Haraway’s notion of ‘companion species’, from her 2003 manifesto, referring to a genuine love and respect for other creatures on their own terms that does not require anthropomorphism. However, Mujinga goes further with her speculations, and her thinking is more in line with science fiction writers such as Octavia E. Butler from the first lines of whose book, Dawn, the gorilla portraits mentioned above derive their title. In a somewhat dystopian post-human vein, Mujinga stated in an interview with Contemporary And (C&), ‘Quite often science fiction is about how we will survive, but Butler is not afraid to say that maybe it’s not our turn anymore’.

The separation, not only between human and animals but also between the living and non-living, organic and artificial, gets blurred in Mujinga’s use of materials. In the performative work Atrophic Giants for the Roskilde Music Festival in 2018, the artist’s ‘elephant ears’ expanded into the silhouette of a whole elephant, mutated to erase the distinction between the epidermal layers by burning acrylic and combining PVC, glycerine and oil paint, resulting in the large flakes of plasticky, singed skin. The same technique was used to create an even larger work, Ghosting (2019), installed like a garish tarpaulin across the exhibition space at Kistefos in Jevnaker for the group show TEMPO TEMPO TEMPO in 2019. This work also incorporated denim, another material Mujinga has used repeatedly, often in combination with other textiles, for instance, in her contribution to the Norwegian Sculpture Biennial, Clear as Day (2017). The title was playfully negated in the performance where models used Mujinga’s oversized, ‘wearable sculptures’ with large hoods to prevent any clear view of their bodies.

Sandra Mujinga, Ghosting (2019). Installation view of Witch Hunt, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen (2020). Photo by Jan Søndergaard. Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, and The Approach, London.

Mujinga’s titles often contain layers of meaning that are sometimes contradictory. Ghosting refers both to the strange presence of this piece of partially melded, burnt, damaged material and to the largely online phenomenon of ghosting, where one simply stops responding to a conversation partner, disappearing like a ghost. By using acronyms for many of her titles, Mujinga also plays with the penchant for minimising characters or the use of absurd hashtags, doomed to fail as one-offs in the prevailing argot of digital culture. Her longest to date is YISIFOTMATABOJTMIDTIPFMBRPMFWWW (2016), which stands for: ‘Yesterday I stood in front of the mirror and told a bunch of jokes to myself, I don’t think I performed for myself, but rather prepared myself for what would come’. A snappier acronym was SONW – Shadow of New Worlds, the title used for the exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall and its accompanying catalogue.

Up until the spring of 2019, my only encounter with Sandra Mujinga was through her exhibited or performed work. Concomitantly with the opening at Kistefos, Mujinga was awarded the first solo exhibition in new series SOLO OSLO, which I had conceived when I took up a permanent position at the Munch Museum. As a curator, one’s relationship with an artist tends to change once they become a future exhibitor. One moves from the outside – as an engaged viewer or fervent admirer – to the inside. One gains a better understanding of the artist’s process, the fine details of the work’s becoming. One loses the approximation of an objective view, a blissfully unaware delight in the finished work.

Subsequently, I viewed every new exhibition of Mujinga’s work with new eyes, focusing on the specifics, doing a mental search head for how this work related to earlier ones I had seen or the one the artist was making for the exhibition at MUNCH, as the museum had by now become known. The SOLO OSLO show was initially scheduled for October 2020, then it was delayed for over a year-and-a-half due to the pandemic and the postponement of the opening of the new MUNCH museum building. Mujinga’s exhibition finally went on display in January 2022.

Since our collaboration started in 2019, Mujinga’s career as an emerging artist has ‘taken off’ as the artspeak-prone actors from You Are All You Need might have put it. Mujinga’s first solo exhibition at her gallery Croy Nielsen in Vienna, Seasonal Pulses, in spring 2019 introduced the hooded, long-legged, flared-trousered figures of Mókó, Libwá, Zómi and Nhámá, ‘named for the order in which they will exist in the future’ (their names translate from Lingala as 1, 9, 10 and 100, respectively). These were also included in the exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall, which opened at the end of 2019 and closed just before the pandemic restricted freedom of movement at the start of 2020.

Sandra Mujinga, installation view of Spectral Keepers at The Approach, London (2021). Photo by Lewis Ronald. Courtesy the artist and The Approach, London.

Sandra Mujinga, Worldview (2021), installation view at the Swiss Institute, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna.

The transportation of works was less impeded, however, and Mókó, Libwá, Zómi and Nhámá travelled together with Flo and Coiling to Vleeshal in Middelburg in the Netherlands as part of a different, smaller version of the exhibition in Bergen in late 2020, before moving on to the Gothenburg Museum of Art in summer 2021. At the same time, the Nokturnal Kinship figures travelled to the MOMENTA Biennale in Montreal, together with Disruptive Pattern; Ghosting travelled to a group show at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen; and Octo Clutch/Temporary Home made an appearance at Nottingham Contemporary in the UK. Mujinga’s practice encompasses far more than I could hope to address in this one text, and many of her other works also made their way across land and sea to reach other audiences.

Mujinga produced a number of new works during the pandemic, including a series of tall, textile-clad figures for the exhibition Spectral Keepers at her London gallery, The Approach. These later travelled to MUSEION in Bolzano, Italy. In May 2021, Mujinga premiered her three-screen work, shaped like windows, for her solo show, Worldview, at the Swiss Institute in New York.

Just days later, Mujinga was awarded Sandefjord Kunstforening’s Art Prize of 200,000 NOK for the video triptych Pervasive Light (2021), which was subsequently included in the New Museum Triennial in New York at the end of October 2021. That same month, Mujinga was awarded the prestigious Preis der Nationalgalerie.

Sandra Mujinga, installation view Preis der Nationalgalerie, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin (2021). Photo by Jens Ziehe. Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, and The Approach, London.

Sandra Mujinga, Pervasive Light (2021), installation view of Soft Water Hard Stone at the New Museum, New York. Photo by Dario Lasagni. Courtesy of the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna and The Approach. London.

In her nominee exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, Mujinga showed two new works: Sentinels of Change (2021) and Reworlding Remains (2021). The former, a floor-based installation, included the remains of some imagined prehistoric creature, watched over by a tall figure, draped in overlaid textiles, like basketweave or crocheted shawls. One of the guards stood over a welded metal-rod construction with tattered fabric hanging from its frame. According to the artist, the weaving of the textile with its frayed ends suggested a skin that could either be growing anew or on the brink of collapse; and the shape, an outline of a dinosaur, acted as ‘a speculative site to imagine new bodies’, going backwards in time in order to reconceive the future. In the next room, three further sentinels hovered ominously like spectres of death, more bedraggled and disturbing than their figurative relatives in Mujinga’s other works, Spectral Keepers, Nokturnal Kinship and Mókó, Libwá, Zómi and Nhámá.

Alien invasion at MUNCH

In Mujinga’s new commission for MUNCH, there are elements that can be traced back to other exhibitions in her oeuvre. The triptych videos from Sandefjord Kunstforening and the New Museum Triennial have expanded into a larger, three-dimensional trio of Plexiglas cubicles. The material harks back to the semi-transparent Plexiglas of earlier works such as Camouflage Waves 1–3 and Stretched Delays 1–4. In the vast space on level 10 of MUNCH, however, the opaque planes serve as a projection surface that refract and blur the animated figure. The result of a collaboration with designer, Saphira Nancy, Mujinga’s new figure has antecedents in Flo, in its strange muscularity, but also in the ‘deep sea’ works with the mermaid and octopus. The animated sequences are projected from the mouths of three monster-like figures, their metal scales offering a departure from Mujinga’s usual penchant for textiles and glycerine/PVC compounds as approximations of skin. Nonetheless, the anthropomorphism of both the monsters and the animated figure remain, though they depart even further from any concrete resemblance to humans. Described as ‘an alien invasion of the office’, Mujinga has created hybrid creatures that might equally belong on the seabed or in the realm of the extra-terrestrial. The artist’s characteristic use of green light figures again in this exhibition, erasing the contours of the space as it meets the darkened floor and walls. The artificial corridor Mujinga has added to the gallery on level 10 at MUNCH resembles the one she created for her exhibition Worldview, where she reconfigured the basement space at the Swiss Institute. The extra hallway at MUNCH, however, has the addition of one-way glass, which plays with who gets to look at whom as visitors enter the installation. The gentle soundtrack of synth and strings, resembling that of Flo, adds a subtle auditory dimension to this new installation. Where did this creature come from? What has it seen that makes it run? What tales from beyond the abyss might it narrate?

As Gabi Ngcobo noted in her text for the Berlin Biennale:

Addressing history in the present is to speak to a future unknown. Belonging to the generation of the current moment, we cannot immediately understand, in relative opacity, how the events of the present will affect our futures.

Like Jemisin’s orogene, Sandra Mujinga’s work might offer an indication of the impact of the events of past and present on the future. Although disturbing, this power to ‘sess’, however speculative it might be, is to be treasured as a route to greater insight into the here and now. For every new work, standing on the shoulders of its forebears, Mujinga opens up uncharted vistas of understanding and new routes to reflection.

The exhibition SOLO OSLO: Sandra Mujinga is on display at MUNCH from 22 January to 3 April 2022.

Cited works (in order of citation)

N.K. Jemisin, The Fifth Season (2015)

Sandra Mujinga, ‘You Are All You Need’, in Sandra Mujinga, SONW – Shadow of New Worlds (2020)

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome, dir. George Miller and George Ogilvie (1985)

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (1997)

Gabi Ngcobo, ‘Dear History, We Don’t Need Another Hero’, catalogue 10th Berlin Biennale (2016)

Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (2020)

My Octopus Teacher (film), dir. Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed (2020)

The Octopus (La Pieuvre) (film), dir. Jean Painlevé (1927)

The Love Life of the Octopus (Les Amours de la Pieuvre) (film), dir. Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon (1967)

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (2003)

Octavia E. Butler, Dawn (1987)

Sheila Feruzi, ‘Manoeuvring Through the Dark with Sandra Mujinga’, C& (14 January 2020)