It’s about creating what I want to see in the world

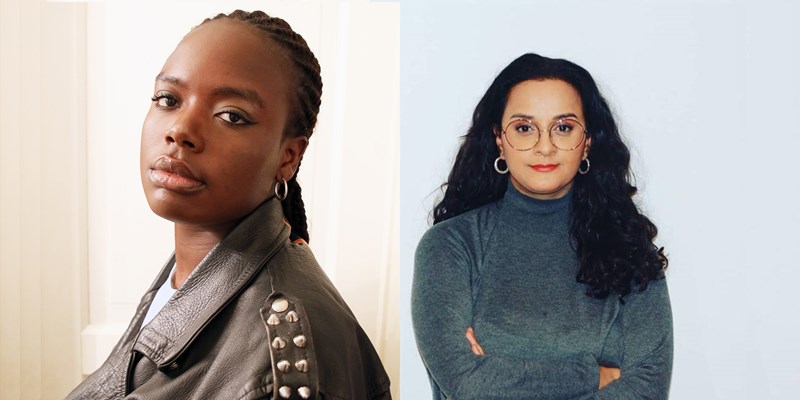

A conversation between Sandra Mujinga and Zeenat Amiri.

Photo: Sjur Einen Sævik og Ole Magnus Higdem Waaler

SOLO OSLO is a series of solo exhibitions at MUNCH, giving newly established artists and mediators the possibility to develop their practice. First out – artist Sandra Mujinga (b. 1989) and mediator Zeenat Amiri (b. 1988).

Mujinga has previously exhibited at renowned institutions such as the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin and the Swiss Institute in New York. She has also won several international art awards. Here she is in conversation with Amiri, an art mediator at MUNCH, about art mediation, visibility, science fiction, time machines, mindfulness, and fashion – and what made her chose art.

The conversation took place on Zoom November 25, 2021.

ZA: Zeenat Amiri

SM: Sandra Mujinga

Before we started recording, Sandra and I talked about the sense of smell and sensory experiences, and about the feeling that our ancestors are communicating with us through memories. This chat about our backgrounds and about the experiences that have shaped us naturally led to questions about representation and visibility, about the relationship between wanting to be seen and having the possibility of hiding.

ZA: You never really get seen for who you are, but maybe through a blurry filter. Is there a difference between who you are as a person and who you are as an artist?

SM: That’s an interesting question, this issue of who you are privately and who you are publicly. I feel like social media is important for me in being able to control the level of personal visibility.

ZA: You’ve said you want to clone yourself. How’s that?

SM: Imagine twenty copies of me standing in front of you and you have to choose the “real” version. That’s a way to be highly visible and at the same time invisible. That’s how I think of social media: a place where I have space to show different versions of myself and at the same time feel very private.

ZA: That makes sense – because you can choose to hide amongst the twenty versions. Or are they all equally authentic versions of you?

SA: All the clones are versions of me, but...When you’re faced with them it becomes a conscious choice in terms of what you decide to focus on when you decide who’s “real”. I’m aware of an inner conflict; as a dark-skinned black woman I want to be visible and I feel a responsibility to be visible, because we’re so underrepresented. At the same time, I want to be visible in a way that lets me hide away. A solution is to show different aspects of myself, show that I’m complex, that I’m lots of things at the same time.

ZA: That there are several copies of Sandra out there.

SM: There’s an insistence on the complex, having several bodies. Which is something I talked about a lot in earlier works. Something else that interests me is the concept of an avatar, where you empty yourself of content so that someone else can build on you. It’s a job you do, at least if you think about tokenism, for example. (Tokenism is a symbolic or superficial inclusion of underrepresented groups, where people with a minority background are recruited to give an external impression of equality. Ed. Note). It’s almost like you have to empty yourself to be a token and represent all melanin rich people. I’m now in a position where I can say “no, I don’t want to be a token”, a symbol, but that’s a privilege – I’ve not necessarily had a choice before. I’m very interested in consent and choice: to what extent are you actually free to make your own choice?

Something else that interests me is the concept of an avatar, where you empty yourself of content so that someone else can build on you.

ZA: When you say privilege, are you thinking of your position in the art world and the power that comes with that?

SM: Yeah.

ZA: Yeah, absolutely. You collaborate quite a bit with others and a priority for you is inclusivity and broad representation, I’d say. What part does this play in your artistic practice, the issue of representation?

SM: For me, art is mainly about creating what I want to see in the world. So, representation plays a huge part in that. I’ve experienced not being able to find dark-skinned black models through modelling agencies and agents, because it’s totally white. That makes it easy to jump to the conclusion “oh, no, they don’t exist”, but of course they do. When I’m at Oslo City, I see –

ZA: There they are!

SM: Yes! So, representation is about having a bit of a DIY attitude. And because I often work with people outside the art sector it’s important for me to find long-term collaboration. You know when people are like “any questions? No? Fine.”

ZA: Done. Finished. Go!

SM: Yeah, exactly. That’s not me. I hope my art can create a space to think out of the box. It takes a long time before people know which questions they want to ask, or what they actually want to find out about. Being able to establish an ongoing or long-term collaboration is important to me. I associate it with consent. If you can work with people where they are, I don’t want to miss out on that opportunity, even though it obviously takes more time, energy, and resources on my part, as well.

ZA: I understand. I think that real representation is about building relationships.

SM: Yeah.

ZA: Do you remember your first experience of art?

SM: Possibly my mum’s drawings? But they had a clear function: mum used drawing as a tool, making drawings for fashion. So, I often wonder if this was my first experience of art? Or was it an experience of tools? I’m always confused about this. Because art can be a tool to get access to more parts of yourself and the world, but there are also tools that can be seen as art later.

When I visited the Vigeland Park as a kid, the sculptures were presented as art. Mum’s drawings could have been exhibited, and you could have seen her creativity, but instead it was seen as a tool to carry out something else, like a dress. So, it’s also about a Western idea of what art is and who has the power to define that. I grew up with African masks and works, art from the Congo, and it’s interesting that you can be surrounded by art, but not think of it as art.

ZA: Because it’s not displayed on a gallery wall. I thought about something the other day, that in Eastern cultures you’re surrounded by art without knowing. You make art without knowing. You have access to the tools without knowing it. But in the West art is kind of separate from life.

SM: Yeah, that’s really interesting. Here art is seen as a thing you do, an interest, but other places it’s part of the essence of the community. You’re surrounded by it and it’s accessible. It’s not about ownership.

I hope my art can create a space to think out of the box.

ZA: In terms of your path into art – you were surrounded by art already from childhood, your mum sewed and stuff, but why did you decide that art was something you wanted to go for?

SM: I tried everything else before that.

ZA: You did?

SM: Yeah, believe me. I applied to study architecture, but didn’t get in. Tried fashion. I did everything. My first dream was to make animation films, that was after I saw Lion King. So, art felt far removed. In year 11 I took a career test. I scored high for everything and was interested in most things. The only thing I got a low score for was carpentry. After attending Einar Granum (an art school in Oslo. Ed. Note.) there was a teacher who suggested I study art and when I applied I got into several academies. In a way, art gives me space to be lots of different things: I can use maths, be interested in architecture, try my hand at carpentry.

ZA: Ok, so now we’ve talked about claiming your space in the art world, privileges, and power. But, bloody hell, in the last few years you’ve just been like bam-bam-bam-bam! You’ve met the king; you’ve won international prizes! You’re up there, you’re international. You often bring up visibility and invisibility in your art. What do you think about that now?

SM: In Camara Lundestad Joof’s film Already here I talked about not wanting to be the first. Being the first is often presented as a privilege.

ZA: It can be a burden.

SM: Yes because it’s about what the space was before you entered. So much is based on certain specific bodies, and where these bodies become a norm. If there’s no reflection on this, my job becomes to fit in, rather than making the space diverse. It becomes another task. Being able to be yourself becomes something you have to insist on. Musti raps about the same thing, about being yourself!

ZA: Yeah, that’s true!

SM: Being yourself isn’t a given.

ZA: Especially not in a white space. But now you’re in a position to say: “fix this and maybe I’ll be back.”

SM: Yeah, exactly!

ZA: But while we’re on the topic of white spaces...how did you end up living in both Oslo and Berlin, and becoming part of the art scene there?

SM: When I was at the art academy in Malmö, the school had a flat in Berlin that you could apply to stay in and where you could work on projects. That meant I got a lot of close connections and friends in Berlin that I wanted to maintain. Also, I felt the need to get out of Norway and study abroad. It’s about building your own thing. As a child you notice when you’re surrounded by adults who believe you can make something of yourself.

ZA: I never noticed that, sorry, haha.

I love the fact that representation can affect us in the way that it actually changes our lives.

SM: Exactly, you notice the people who believe in you and those that don’t. Some kids got “you’ll be prime minister one day” and others just got “stay out of trouble”. That’s based on stereotypes of black kids, and it’s also about class, of course. Having people pat you on the shoulder and say “wow, your Norwegian is so good” in a patronising way – that says a lot. When you’ve grown up with there being no expectations of you, you realise the minute you finish school you just want to get some distance from that. That’s how I could build myself up and have my own goals and ambitions. It’s not just about Oslo, it’s about the whole world.

ZA: Miss International!

SM: Low expectations can also be unhealthy. It’s a bit like when Audre Lorde talks about having to write stories about herself, because if she let others write stories about her she’d go crazy.

ZA: I love the fact that representation can affect us in the way that it actually changes our lives. We have the power when we get away from the claim “you have the potential, you have to use it!”

SM: Yeah, that comment: “You have potential”, that’s exactly it.

ZA: “What are you doing with your potential?!”

SM: Oh, my god. Potential is like slamming on the breaks. It gives you hope of advancing, but it’s actually like, “this is as far as you go, love, this is what your potential amounts to!”

ZA: Exactly. I think it’s great that you can write your own story, because it’s like distancing yourself from the “potential” they see and understand, which is only a fraction of you. I’ve also noticed what you mentioned before that it’s patronising. But on to the next question! What is it about science fiction that attracts you and how do you explore it in your art?

SM: This comes back to what Audre Lorde said, as well, about writing your own story. I saw a meme once that said: “black people don’t fuck with time machines.” So, that means you’re thinking of a time machine as something that takes you back in time, right? There’s something transformative about really giving yourself the space to imagine alternative stories in relation to the black body. There’s also the possibility of shapeshifting, change form, really imagining other political landscapes and personal relations, not limiting yourself through structures born of colonialism. This makes me think of the beginning of N. K. Jemisin’s novel 5th Season, “Let’s start with the end of the world, why don’t we? Get it over with and move on to more interesting things.” I think sci-fi gives us the space to think about our own limits as humans.

ZA: That sounds like a much more appealing way to explore our own stories, or new stories, rather than going back in time. So many people romanticise the past: “I would love to go back to 1920!”

SM: No! That’s why I don’t get retro fashion! I’m not going back to the 1960s.

ZA: You can like travel back in time as a white man. Speaking of fashion: you’ve previously worked a lot with textiles, but right now I’m more interested in how you express yourself through fashion? I feel like you use fashion as a superpower. Am I reading too much into it or are you also using fashion and textiles to express yourself artistically?

SM: I look at fashion as data, I’d say. That’s why I find fashion history fascinating. And I keep an eye on fashion. It’s always there in the background, even when I’m working on my sculptures. I can use fashion to speak without words. That’s what fashion does for me. I can stand there totally relaxed without saying a word, but still saying a lot. I think there’s something magical about that. And my mum plays a big part in this, of course. She bought me cowboy boots when I was still in primary school.

ZA: Goals.

SM: The other kids were like: “whaat, why are you wearing those weird shoes?!” I’ve always been very conscious of clothes. But then I’m Congolese, as well, though!

ZA: Mhmm.

SM: When you go to Kinshasa, you might meet someone who wears the same dress every day, but that’s like a really nice dress. It’s about communicating and having the responsibility of showing beauty on the streets.

ZA: But Sandra. If someone asked you: “who is Sandra Mujinga?” What would you answer?

SM: Well, it’s kind of sad because I immediately think of what I do. It’s very interesting. It hasn’t always been like this – that you talk about your CV when you want to tell people who you are, but these are the times we live in. So, who is Sandra Mujinga? I’m a super serious, ambitions, goofy person.

ZA: Love!

SM: Lately, I’ve thought a lot about how I’ve always been very ambitious in everything I do. I think it’s about caring. When I do something, I want to do it properly. I really want to be present. And it’s an ambition of mine to always show mindfulness in everything I do. That it means something. I want to continue caring about things. It’s not something you can take for granted, because you can get pulled in all directions. I care about everything I do. Friendships, too.

ZA: I don’t remember who it was, but someone asked me “what do you do, outside of work?” and I was like fuck, what do I do? You put so much into your work that it’s a bit like, who am I really?

SM: Yeah, it touches on internalised capitalism, which is very real. We’ve spoken a bit about this, really considering “what’s important to me?” without it being about what you produce and do for work. You have to practice this all the time. I think music has really helped me with this. When I make music –

ZA: The music?

SM: Yeah, the music I’ve produced myself, like for example my project NaEE RoBerts. I was listening to it on the bus the other day and I was like... it makes sense that I make the sculptures I do, because I’ve always worked with strings and big soundscapes. That the same elements pop up in my sculptures as well. It’s almost like the music is the precursor to the sculptures. When you’ve heard the music, you can imagine the bodies that will emerge in the future.

ZA: Wow, that’s so interesting, ‘cause we talked about this in relation to cooking earlier. And this thing about sense of smell and what scent does to us, cooking without a recipe, but with your heart and senses, that there’s something guiding you; the ancestors are like “ok, enough spices now.” Do you feel that the music works in the same way, through these objects?

SM: The thing about the ancestors is so fascinating. They are real to me. When I read about what the Congolese people went through under Belgian rule, or what some individuals have survived – this is real to me. I bring this with me, and it gives me a kind of strength. It’s almost religious. And this is how I think of the past. That it’s an interesting approach when I’m working on the future. It’s our responsibility to preserve the ghosts of the ancestors, or to live with them in a different way. You can look to the past but have hope for the future.

The exhibition SOLO OSLO: Sandra Mujinga is on display at MUNCH 22 January - 3 April 2022.