Apichaya Wanthiang – towards an exhibition history (2012–2022)

In this essay, curator of contemporary art, Tominga O’Donnell traces their experience of Apichaya (Piya) Wanthiang’s work and how some of the ideas that emerge in the artist’s solo presentation at MUNCH have antecedents in her earlier exhibition practice.

There are many elements from Piya Wanthiang’s exhibition practice that come together in her new commission for the SOLO OSLO series at MUNCH. The two-part installation draws on her previous work with performance, painting, architectural constructions, light, social histories and personal narratives. Attentive to Frida Rusnak’s mediation project with blind and partially sighted young people, Wanthiang has created a multilayered work that addresses the body as whole, eschewing the primacy of vision that characterises the medium she is perhaps best known for – painting.

More about the exhibition SOLO OSLO – Apichaya Wanthiang

My first encounter with Piya Wanthiang’s work was at LNM – the Association of Norwegian Painters in her exhibition there in 2018 entitled Driftwood and Ghost Hunters. Having completed a PhD on the spatial dimensions of exhibitions just a couple of years prior, I was struck by Wanthiang’s novel use of display structures for her paintings. They were clearly sculptural, a kind of three-dimensional wooden support that expanded the two-dimensional planes of the paintings with material resonances in the bespoke seating for the exhibition. Sharp corners jutted into the rooms at LNM, obscuring the view into the next gallery and creating a clear demarcation from its interior with stucco detailing.

Apichaya Wanthiang, Driftwood and ghosthunters (2018). Installation view at Landsforeningen Norske Malere, Oslo. Photo by Niklas Lello. Courtesy of the artist and LNM.

By partially blocking doorways and creating non-spaces, Wanthiang was deliberately ignoring the traditional ‘enfilade’ (sequential) arrangement of galleries in late 19th century private dwellings. The paintings themselves were lush, rich in colour and depth, depicting a landscape far away from downtown Oslo. Here were huts on stilts that one might associate with vernacular architecture in South-East Asia. Thick vegetation in a range of green hues suggested a tropical climate, the ground wet and muddy. Apart from the houses, the rural scenes were devoid of people, creating an ominous post-apocalyptic scene, underscored by the use of abstraction, providing a multicoloured surface project your own fantasies and fears. In fact, the paintings were inspired by images of the currently flooded fields in Wanthiang’s birth country, Thailand.

Shortly after Driftwood and Ghost Hunters, Wanthiang opened another solo exhibition in Oslo, this time at UKS (the Young Artists’ Society). Evil Spirits Only Travels in Straight Lines revealed was entirely different: an immersive installation, ‘a habitable place for lingering spirits’, in the artist’s own words.(1) Entering the galleries through a corridor of green textiles, hanging off Wanthiang’s characteristic wooden support structure, visitors encountered several mounds of clay, lit from below with LED strips that gently pulsated as if the sculpture was breathing slowly.

Apichaya Wanthiang, Evil spirits only travel in straight lines (2018). Installation view at Unge Kunstneres Samfund, Oslo. Photo by Jan Khür. Courtesy of the artist and UKS.

The mounds were heated, and one could lie down on the largest two and feel the warmth of the ground temperature of Wanthiang’s childhood village in Thailand. The installation also included videos of the artist and her aunt performing a Buddhist ritual of feeding the dead, and apparently real-time footage of mayflies near her grandparents’ house. The exhibition was available for two hours every day precisely at nautical dusk in Oslo, which coincided with when the installation could best be seen from the outside, in other words, when it was most welcoming to visitors. This temporally-based rule of access was reminiscent of an earlier work featuring the sunrise in Thailand, transmitted live, which Wanthiang presented at Visningsrommet USF in Bergen in 2014 under the title Without Waiting For Her Reply (WWFHR). Because of the time difference, the exhibition was open from 11pm to 3am Norwegian time.

Apichaya Wanthiang, Without waiting for her reply (2014). Installation view at Visningsrommet USF, Bergen. Courtesy of the artist.

This commitment to a synchronised live moment, despite geographical distance and the circadian rhythms of local audiences, suggests not only a strong artistic commitment to a conceptual premise but a genuine longing to be in two places at the same time. It is a feeling anyone who has migrated might relate to: the sensation of never being quite at home anywhere. Not even in your ‘native’ country.

Wanthiang defines the notion of synchrony as ‘being attuned to something or someone’. In her first painting exhibition at Galleri Brandstrup in Oslo in 2021, entitled When the First Thought is Touch, she took the idea further. Here, synchrony included repetitive, mundane tasks such as cooking and cleaning, as well as rhythm and ritual. Chanted mantras and other ritualistic acts connected not only people performing them in the present, but also ‘binds us to those who have performed those same gestures in the times before us.(2) This kind of synchrony implies not just happening in two different places at the same time, but also something that could travel across time, affecting bodies that are both temporally and geographically remote from each other. The connection could be transmitted in time and space, creating a bond with past and future generations, and people in different places.

Apichaya Wanthiang, When the first thought is touch (2021). Installation view at Galleri Brandstrup, Oslo. Photo by Øystein Thorvaldsen. Courtesy of the artist and Galleri Brandstrup.

An explicit reference for When the First Thought is Touch was the book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (2014) by Bessel van der Kolk. In it, the Dutch psychiatrist and trauma researcher, discusses the somatic effects of post-traumatic stress and potential forms of healing as alternatives to traditional cognitive behavioural therapy or exposure therapy. These include the somewhat controversial practice of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), yoga and a form of roleplay called structure’, a psychomotor therapy derived from dance. The relevance for Wanthiang’s work is the argument that trauma is something that affects the body directly, bypassing the brain and evading capture by language. This kind of theoretical source material is seldomly found explicit in Wanthiang’s exhibitionary practice, but instead seems to hover in the background, creating an ineffable sense of the work somehow “dealing with” trauma. The transactional connotations of the term “deal” – which artists and artworks are often cited as doing – is perhaps apt. Tapping into experiences of trauma costs and need to be worked through over time.

In When the First Thought is Touch, Wanthiang again worked with innovative display structures for her paintings, this time replacing green timber with reclaimed steel poles. With a nod to the prevalence of plastic barriers during Covid, Wanthiang and architect Nicolai Ramm Østgaard opted for semi-opaque polycarbonate sheets with an undulating surface, which blocked sightlines and provided each painting with its own intimate space. The colour palette of the paintings departed from the lush greens of her earlier exhibitions, and reflected instead the explicit inspiration of this body of work: Indian news imagery showing funeral pyres of Covid victims. Blown-up in size and made abstract through Wanthiang’s energetic brushstrokes, these paintings were not immediately recognised as referring to the harrowing news footage that inspired them.

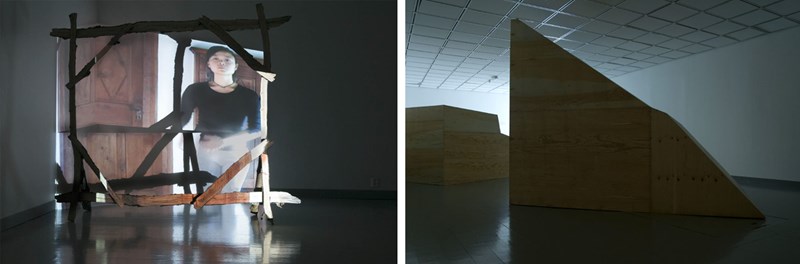

The three Oslo exhibitions have clear antecedents in her previous shows. Wanthiang studied in Bergen and was given a solo show at Hordaland Kunstsenter in 2012. For Geography of A, Wanthiang combined an enveloping installation of plywood structures, a video of her dancing and a soundtrack of stories of migration between Thailand and Belgium – a journey she too had made as child.

Apichaya Wanthiang, Geography of A (2012). Installation view at Hordaland Kunstsenter, Bergen. Courtesy of the artist and Hordaland Kunstsenter.

The immersive multimedia approach, the architectural components, the centrality of storytelling and the presence of the breathing body are all aspects that have remained central to Wanthiang’s practice over the last ten years. These elements were also present in projects such as the outdoor installation All Digressions Aside at Barents Spektakel on Norway’s northeastern border with Russia in 2016. Here, Wanthiang worked with long-term collaborator, architect Cristian Stefanescu, to design two ‘storytelling huts’, one in Kirkenes on the Norwegian side and one in Nikel on the Russian side, complete with fireplaces necessary for the time of year in the polar north. When someone entered a hut and stoked up the fire, a temperature sensor would trigger a live stream of stories from the parallel hut: voices telling stories Wanthiang had gathered from each town. In this way, a direct dialogue was created, – geographically and across time, with stories having passed down through generations.

Apichaya Wanthiang, All digressions aside (2016). Installation view at Barents Spektakel in Kirkenes, Norway and Nikel, Russia. Courtesy of the artist.

The last decade has seen Wanthiang show her work across the whole of Norway: from Kirkenes in the North to Kristiansand in the South, and not least in Bergen on the West coast. In 2017, Kunsthall 3,14 in Bergen staged the exhibition While the Light Eats Away at the Colors, a display of eight large paintings, which preceded the LNM show a year later.

Apichaya Wanthiang, While the light eats away at the colors (2017). Installation view at Stiftelsen 3,14, Bergen. Courtesy of the artist.

Although their subject matter was different – inspired by a study trip to France that included a visit to Henri Matisse’s Chapel at Vence – the paintings revealed Wanthiang’s penchant for capturing the lushness of landscapes with her acrylic paints, including at night, in a range of deep blues, greens and reddish-browns. The canvases were strung up on wooden frames like the ones at LMN, which deliberately challenged the neoclassical lines of the gallery spaces in the former grand bank building, erected in the 1840s. The specially-designed seating was made from the same green lumber that Wanthiang used for the frames, and dictated the placement of viewers in the space.

For her exhibition at Kristiansand Kunsthall in 2020, I’ve been here before, Wanthiang supplemented green lumber with reclaimed wood and new planks. She built a large structure, with stairs on each side, that seemed to function as a watch tower, clad with painted planes and with small, openings onto the surrounding gallery space. A strange, long bed, snaking its way from the tower, arrived at a makeshift tent, not unlike the soft hideaways children make with blankets at home. Making use of all the spaces in the Kunsthall, Wanthiang once again choreographed visitors’ movements around her installation. I’ve been here before triggered memories with its fouand materials – the open staircase of the artist’s grandmother’s house, where she used to play as a child; or the pinewood bedposts typically found in 1980s Norwegian homes.

Apichaya Wanthiang, I’ve been here before (2020). Installation view at Kristiansand Kunsthall, Kristiansand. Courtesy of the artist and Kristiansand Kunsthall.

While these constructions had a temporary, even rickety quality, Wanthiang has also created permanent public commissions in recent years. Her first was for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences – Campus Ås in 2020, where she created a large painting installation for the walls of its triple-height concourse. Inspired again by the flooded rice fields of her grandmother’s village, Wanthiang created the work by throwing buckets of paint over MDF surfaces, allowing the water to evaporate from the paint and dry in bright patches of colour. The MDF was cut into organic shapes and mounted on three walls of the campus building, leaving gaps so that the walls seemed to be covered by a large, colourful mosaic. The shapes were echoed in the seating Wanthiang designed as part of the commission, in keeping with her previous temporary painting exhibitions.

The relationship between liquid and evaporation was also central to Wanthiang’s next commission for Ruseløkka School in Oslo in 2021. Here, she created ten large-scale frescos, painted directly onto the concrete walls of the school’s central staircases, across seven floors. Each wall showed Wanthiang’s impression of different landscapes, including from Thailand, Norway, Vietnam and Tanzania. Entitled Of All the Places I have Gone and have yet to go, the work was inspired by both real and imagined landscapes, taking students using the stairwell on a sensuous journey where the scene shifted on each landing. Painted with great physical effort, which left its toll on the artist’s body, the Ruseløkka commission is typical of how Wanthiang approaches every new project: a huge amount of intellectual and physical labour in order to achieve a result that affects the viewer immediately and viscerally.

Apichaya Wanthiang, Of all the places I’ve been and have yet to go (2021). Commissioned murals at Ruseløkka Skole, Oslo. Photo by Trond A. Isaksen. Courtesy of the artist and Kulturetaten

Oscillating between personal and large-scale societal events is also something that recurs in Wanthiang’s practice. The temperature might be the same as in her childhood village, and the flooded rice fields might resemble the ones in her grandmother’s region, but at the same time the works refer to something more general. They point to the devastating effects of climate change – rising temperatures, torrential rainfall – which increasingly impact the whole planet. The works on mourning and memory may be sparked by the artist’s own experience of loss, but they leave gaps for the viewer to fill with their own lived experiences. There is also the poetry of Wanthiang’s exhibition titles, which invites the imagination to go on a journey without shutting down the possibility of individual interpretation.

Some Body Else at MUNCH

The gallery on Level 10 of the museum is my favourite space. It is an oddly shaped single room, approximately 250 square metres, with a soaring 8 metre high ceiling at one end and a low, head-bumping height at the other. It is a space that offers immense opportunity, but also makes tough demands on any artist tackling it. Wanthiang was selected for the second SOLO OSLO exhibition at the same time as the first, Sandra Mujinga, in the early summer of 2019. This solo presentation has, therefore, been a long time coming after Covid-related delays.

Looking back on the notes from my earlier conversations with Wanthiang – which is ample as this is an artist who approaches each project with meticulous planning and considerable intellectual and material reflection – it is clear from the beginning, that she wanted to create a sense of entering a body when stepping into the space. She wanted to orchestrate two different atmospheres inside this body: one calm, the other more stressful. Programmed blinking lights would contribute to the different environments. From the beginning, a guiding concept was the idea of the ‘transmission of affect’ from one body to another. Teresa Brennan’s notion of bodies not being self-contained, in her book The Transmission of Affect (2004), was a constant reference point. Brennan argues that emotions and energies are not contained by the skin, but impact bodies physically. Brennen uses the example of walking into a room and sensing an atmosphere, and argues that this transmission of affect does something to your biochemistry and neurology. Thus, your body is not a separate entity that your mind controls, but it responds to the experiences of other bodies on a physical level. In that sense, it is an extension of the argument that van der Kolk made in The Body Keeps The Score. Not only does trauma act on the body directly, but that one body’s trauma can affect another – directly on a purely somatic level.

There is an immense tactility in the materials Wanthiang has chosen for this commission. Their texture – a coloured mix of agar and glycerine – is incredibly tempting to touch. Agar is a gelatinous substance that takes its name from the Malay for the red algae that produces it (agar-agar). It is most commonly used as a vegan substitute for gelatin in cooking, but it is also used in the medical industry.

I have only seen it used by an artist once before, when Michel Blazy used it as a decaying ‘wall painting’ that gradually peeled off the interior of the Centre Pompidou in thin dried sheets, and gathered in small piles like discarded bonito flakes. Agar is an inherently unstable substance for artworks, and I was reminded of the decomposition of works in latex by Eva Hesse (1936–70). Like Hesse, Wanthiang seems drawn to the organic quality of her repurposed industrial material, while being explicit about her desire for something biodegradable. From a conservation point of view, the use of a material that breaks down naturally provides a challenge, but from an environmental perspective, it is in keeping with an artist who remains profoundly concerned with the state of the planet and its inhabitants.

In Some Body Else, sheets of coloured agar and glycerine hang off specially designed metal frames. They evoke Wanthiang’s mountains, lit from below, in Evil Spirits Only Travels in Straight Lines. Their fleshiness gives them a stronger three-dimensional presence in the space than a theatre prop; instead they are like naturally occurring wind shelters, protecting those who crouch in their embrace. The agar-mix skin that clads the metal shapes are revolting and beguiling. I touch them and shudder, then touch them again. One of my first verbal reactions to seeing them and holding the trembling sheets in my hands were ‘monstrous’. I was reminded of that when I read the following lines from Ocean Vuong – a writer Wanthiang has often cited – in his book On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019):

… monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.3

The agar sheets on the mountainous shapes come in varying degrees of transparency and colour concentration, but are clearly divided into reddish and bluish sections. The blinking lights, programmed by long-term collaborator Sindre Sørensen, enhance the separation between the two spheres. In the reddish area, the lights flash at an alarming speed, and the physical sensation is palpable after a few seconds as a speeding up of the pulse and an unsettling feeling of stress. Moving through the off-white landscape of the carpeted floors into the blueish section, a sense of calm descends. The lights don’t blink any more, but seem to breathe with you as your breath slows. Wanthiang has worked with Kolbjørn Vårdal, an Oslo-based physical therapist with a background in research into trauma and stress and their neurological impact. In a time where much therapeutic contact was conducted via online platforms, it was essential to find a collaborator in Oslo, who could meet physically with the artist. The notion of trauma that has been hovering in the background of Wanthiang’s practice for many years has been made explicit in this exhibition at MUNCH. At the same time as dealing with it directly in the installation, Wanthiang offers respite: breathing exercises that merge traditional Buddhist chanting with stress-mastering techniques designed for treating trauma sufferers.

The final component of Some Body Else is the soundtrack of human utterances that hovers in the background of the space, and moves with visitors as they traverse the soft organic landscape. The soundtrack is made up of strange guttural sounds, incomprehensible melodic murmurs and narrative segments. In the narrative, the artist herself recalls instances of racism she and other Thai women have experienced over the years. It would be wrong to call these ‘micro-aggressions’, as there is nothing minor about them, but that is the term often attributed to abusive comments that fall short of actual physical violence. Together, however, they do great damage. Even if the mind represses them, the body does keep score and will inevitably exercise – if not exorcise – the demons of accumulated aggressions. In Citizen – An American Lyric (2014), poet Claudia Rankine describes snippets of everyday racism she has experienced. She asks other Black friends and colleagues about their experiences and notes that many of them deny having suffered any form of aggression, before getting in touch with her days later – often in tears, because they have allowed themselves to remember.

One of the events Wanthiang describes in her soundtrack to Some Body Else concerns an attack on a Thai masseuse in the Norwegian town of Larvik. When she refuses a customer the sexual services he demands, he attacks her with horrific violence. The inclusion of this event among the ones Wanthiang has directly experienced or witnessed illustrates Brennan’s thesis that affect transmits beyond the immediacy of physical experience. I think it is a point that any member of a minority or vulnerable social group can relate to. I don’t experience racism, but as a queer person I feel the attacks on my communities vicariously. While writing this text, Oslo was the site of a homophobic attack during Pride week, where a gunman opened fire on London Pub, the city’s oldest gay bar. It did not affect me directly, nor anyone I knew, but I had an immediate and devastating physical response. Formal discrimination, religiously-sanctioned hatred and homophobic comments have accumulated to create what a friend of mine referred to a permanent state of internal violence for queer people. Even seemingly innocuous incidents can trigger it.

There is a sense of duality in all of Wanthiang’s projects over the last decade: they refer to both here and somewhere else at the same time. For her exhibition at MUNCH, Wanthiang anchors this duality in the body. Despite having two sections – stress and calm – the effect of the whole installation is to encompass a spectrum of experiences, sensations and responses. That makes it a true representation of life – in all its monstrousness and delight – and a unique experience for anyone who brings their body to it.

By Tominga O’Donnell

NOTES

1) Apichaya Wanthiang, portfolio at https://apichayawanthiang.com/ [accessed 17 July 2022]

2) Piya Wanthiang, https://www.brandstrup.no/exhibitions/when-the-first-thought-is-touch [accessed 18 July 2022]

3) Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019), p. 13.